Atmosphere in Sword and Sorcery and Weird Fiction

I once read a comment online describing one of Walter Gibson’s Shadow novels as “poetic.” Despite being a fan of Gibson’s Shadow novels, I did not consider this accurate. Gibson was not that great of a prose stylist in my opinion. He did other things well, particularly plot, but I would not call his style lyrical or anything like that. I think a better description would be “atmospheric.”

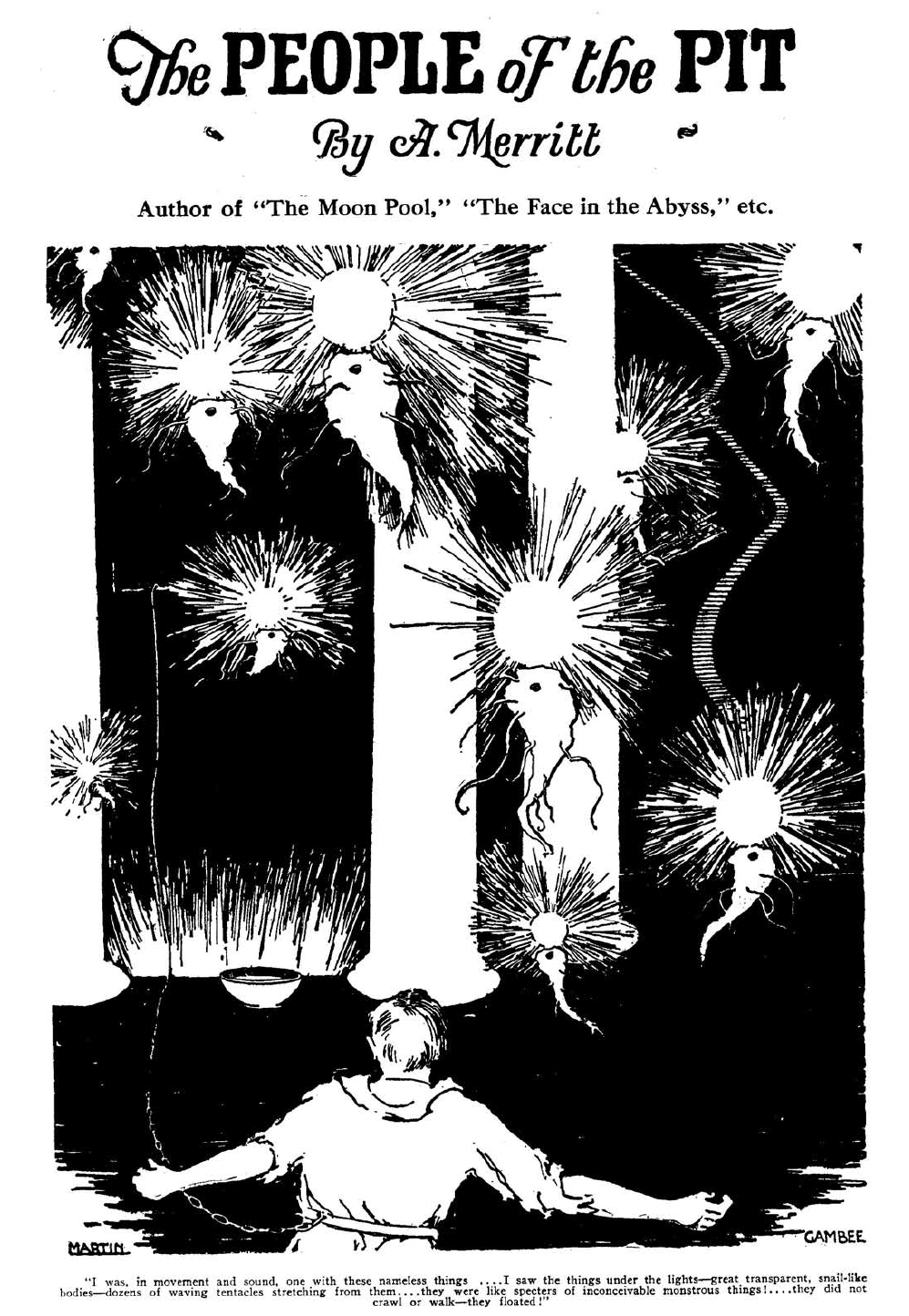

Atmosphere should be distinguished from style. There is a fine line between the two but they are different. Prose style is how a story sounds to one’s inner ear. Atmosphere is how the story makes you feel. You could be good at atmosphere but not a perfect stylist. Though I think some here will dispute this, I don’t think of A. Merritt as a great prose stylist (damn right it’s going to be disputed—DMR) but he creates a weird atmosphere in many of his stories such as “The People of the Pit.” It is in fact, his sense of the alien that is the greatest strength in his work and why he should be better remembered. Not every great stylist is good at atmosphere. To use a non-weird writer, the underrated thriller novelist Ross Thomas wrote the smoothest prose in fiction, but there is not much atmosphere to his novels.

There are of course those who can do both. Clark Ashton Smith, for example, was good at both. H. P. Lovecraft always had good atmosphere and in his later works good prose. Lovecraft in his letters would propose that atmosphere was a key part of weird fiction.

Clark Ashton Smith

This is because weird fiction is essentially about creating a mood. The mood in Lovecraft’s fiction is a kind of fear bordering on the sublime. It is the fear of being small in an almost limitless universe. He is also good at describing decay in, for example, an Innsmouth waterfront.

Smith’s atmosphere is one of the weird and the exotic. Hyperborea and Zothique are almost alien realms. Even Averoigne feels different from the world we know to some extent.

Part of the reason for this is setting. Lovecraft was highly aesthetically sensitive. In his letters he talks with rapturous delight about the architecture of his beloved New England (and actually other places as well.) Since he uses New England for most of his stories he is of course good at describing its aesthetic qualities.

Now here I sort of contradict myself. I think of style as different from atmosphere but frankly they are not that easy to separate. I do however think style influences atmosphere even if they are distinct as concepts and to reiterate I do think you can be good at one and not the other.

One thing that Smith and Lovecraft have in common stylistically is that they break with Strunk and White and use a lot of adverbs. As such they have been accused of purple prose. It is purple prose, but it is very good purple prose. This is no surprise for Smith who was originally a poet. Lovecraft’s prose, in my opinion, was more controlled in his later stories but even in his early stories with their excesses you feel the foreboding.

I won’t say you can’t create atmosphere with more concise writing but I don’t think it would be easy.

What I believe is that atmosphere is in a sense a combination of style and setting.

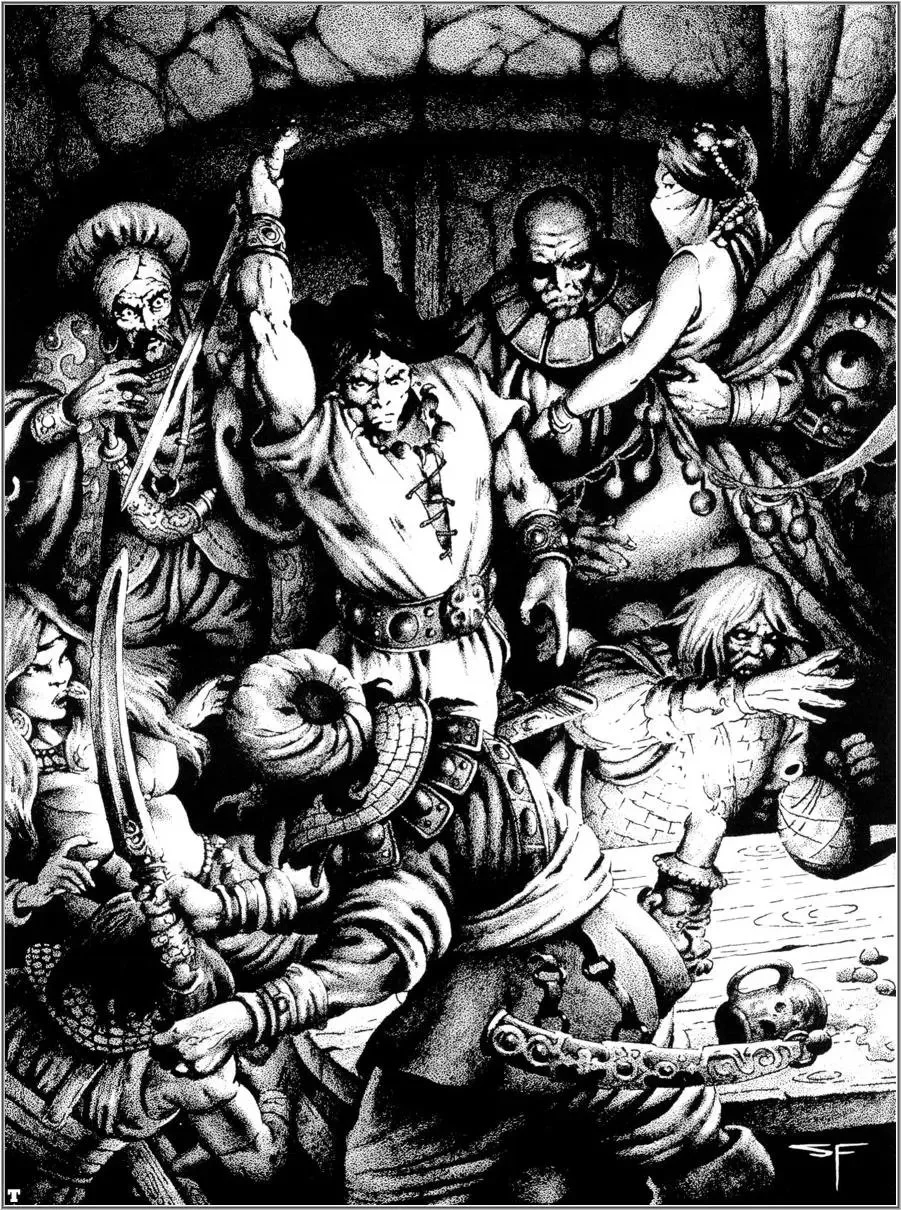

In Sword and Sorcery similar effects can be used. The beginning of one of Robert E. Howard’s best Conan stories, “The Tower of the Elephant,” is a classic example:

Torches flared murkily on the revels of the Maul, where thieves of the east held carnival by night. In the Maul they could carouse and roar as they liked, for honest people shunned the Quarters, and watchmen, well paid with stained coins, did not interfere with their sport. Along the crooked, unpaved streets with their heaps of refuse and sloppy puddles, drunken roisterers staggered, roaring. Steel glinted in the shadows where wolf preyed upon wolf, and from the darkness rose the shrill laughter of women, and the sounds of scufflings and strugglings. Torchlight licked luridly from broken windows and wide-thrown doors, and out of those doors, stale smells of wine and rank sweaty bodies, clamor of drinking-jacks and fists hammered on rough tables, snatches of obscene songs, rushed like a blow in the face.

The language of torches flaring murkily, the name The Maul, the crooked unpaved streets and so on creates a sense of danger in the reader.

Other Sword and Sorcery writers, for example Fritz Leiber, use it to great effect. Leiber’s creation of Lankhmar, the greatest city in fantasy, was a stroke of atmospheric genius. Leiber’s descriptions of the city often involve smoke and fog. These elements of literal atmosphere create a sense of things unseen. He has place names like Whore Street, Plaza of Dark Delights, and so on. All this give a sense of moral corruption. A place where anything can be bought and anything can wait in darkened alleys.

Perhaps of all Sword and Sorcery authors C. L. Moore did strange atmosphere best. In her Jirel of Joiry stories, her heroine often journeys to other realms of existence. In the first story, “Black God’s Kiss,” Jirel descends beneath her castle into what may be hell itself or perhaps another dimension. The descent is claustrophobic but her destination is downright weird. Jirel encounters a woman hopping like a frog and a globe of light with an image of herself in it. These surreal touches add a dreamlike atmosphere to this part of the story. In another tale, “The Dark Land,” Jirel is again transported to another realm from her sickbed. This realm is entirely black, lit by torches. It has a brooding, alien atmosphere to it.

Both the realms have the atmosphere of a fever dream. Something Moore well knew. She mentions in a letter to Lovecraft that she had a sickness when young where she was in a state of delirium. I cannot help think this influenced the strange realms of her fiction.

I think that the atmosphere of the strange realms described in certain fiction might be more valuable than an atmospheric description of a real place. C. S. Lewis in writing about the great weird novels of Mervyn Peake said that they

“are actual additions to life; they give, like certain rare dreams, sensations we never had before, and enlarge our conception of the range of possible experience.”

Lewis, quite rightly, believed a story that added to life was greater than a story that comments on life. Many “realistic” stories are comments on life. These can be insightful comments as in the works of say, Tolstoy, or they can be dumb ones as in the works of many literature majors who should get real jobs. Fantastic fiction more than the realistic kind can add to life.