Like a Thread Through Many Beads

The New Age was never new, not even when it emerged out of the Aquarian ‘70s. Its roots lie nearly a century in the past, with a movement almost forgotten now, but which once exerted a powerful influence over early 20th century Science-Fiction and Fantasy. As I mentioned in my 2023 post “Through A Nighted Abyss”, Theosophy originated in the late 19th century, a blend of mystical traditions of the East and West, a synthesis of philosophy, religion and science. Since I enjoy tracing the origins of ideas, I thought I’d take a look at how Theosophy influenced early writers of Science-Fiction and Fantasy.

The sigil of Theosophy, as it appeared in 1886.

Theosophy emerged from a confluence of many historical factors during the late 19th century. In the realm of science, the new discoveries of fossils—including those of prehistoric humans—had opened up hitherto unimagined realms of “deep time”, as well as casting severe doubts on traditional views of the Earth’s history and Man’s place in it. Before the theory of continental drift became accepted, lost continents were an accepted hypothesis for explaining how fossils of the same extinct animals might be found on opposite shores. Most prominent of these was “Lemuria”, a hypothetical continent in the Indian Ocean which was first proposed by English zoologist Philip Sclater in 1864 to explain the distribution of lemur fossils. A few years later Ernst Haekel suggested Lemuria might have been the birth place of the human race. Lemuria was quickly seized on by contemporary occultists and ended up in the Pacific, where it sometimes vies for space with or is conflated with its fellow sunken continent, Mu. Such are the vagaries of being a fictional landmass with no fixed address.

Spiritualism, which was in part a response against the growing materialism of the Industrial Age, was also a major contributing factor. Europeans had become increasingly aware of religious beliefs from around the world at this time. Once-foreign concepts such as reincarnation were now household words and were being incorporated into Western occultism. India in particular, with its ancient Vedic texts and mix of religions, became a focal point for this new movement. Since most Europeans were still unfamiliar with the Subcontinent, anything said to be associated with it took on an aura of mystical significance.

All these were combined into a single unified form by an aristocratic Russian immigrant, Helena Petrovna Blavatsky.

Helena Blavatsky and the redesigned sigil of Theosophy.

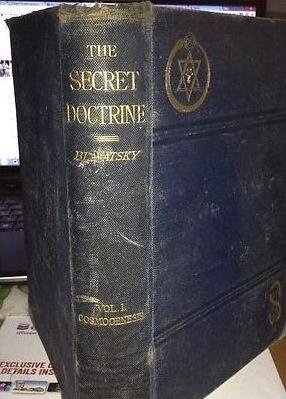

A colorful figure, Mme. Blavatsky’s early life is veiled in conflicting claims. After leaving home at age eighteen, she may or may not have spent time as a circus performer, visited India and Tibet, been a bigamist or a celibate, fought alongside Italian revolutionaries, found Incan gold, been a spy, studied voodoo, and was apprenticed to a mysterious Egyptian occult society known as the Brotherhood of Luxor. Whatever the truth may be, we can say with certainty is that in 1875 she and Henry Steel Olcott co-founded the Theosophical Society. Blavatsky based her teachings on the Book of Dzyan, a mysterious occult text she had become aware of during her alleged visit to Tibet, where she met the Masters of the Ancient Wisdom. From these sources she derived her books Isis Unveiled and later The Secret Doctrine, which become foundational works for the new movement she created, Theosophy, a name she chose from the Greek words for “divine-wisdom”.

Later, William Scott-Elliot, a Scottish amateur historian and theosophist, expanded on her ideas in his two books, The Story of Atlantis (1896), and The Lost Lemuria (1904), later combined into a single volume in 1925. I find that while Blavatsky originated many of these ideas, writers were far more likely to have learned them from Scott-Elliot. And as I wrote this, I found myself quoting the latter far more than the former. Perhaps it’s because, frankly, I found reading Blavatsky’s opaque prose a chore.

Before we proceed we need to become familiar with two of the core elements of Theosophy, the Root Races of Man and the elder continents where they lived.

The First Root Race (Polarians) is said to have been born millions of years ago in the “Imperishable Sacred Land” once found at the North Pole. Keep in mind this was written in the era before the poles were explored and mapped and were regions still veiled in mystery. The Polarians were purely spiritual entities, lacking physical form.

The Second Root Race dwelt in Hyperborea, a name taken from Greek mythology, “the land beyond the north wind”, sometimes identified with Britain or Kazakhstan. Hyperboreans were not yet wholly physical, though they had a yellow-gold hue.

The Third Root Race evolved in Lemuria, as discussed before and will be discussed in more detail later. Some of them are supposed to have migrated to the mysterious Asian city of Shambhala (rendered “Shamballah” in those days), which Blavatsky claimed to be in telepathic communication with.

The Fourth Root Race dwelt in Atlantis which needs no introduction. Various sub-races of the Atlanteans relevant to this discussion include the Tlavati, the Rmoahals and the Toltecs.

The Fifth Root Race, the Aryans, were said to be the current race, and were divided into a number of sub-races which are the various ethnicities of the present day. More on this later.

The Sixth and Seventh Root Races are yet to evolve. The Sixth is supposed to emerge from California in the 28th century, while the Seventh will evolve on a new continent that will rise from the waters of the Pacific in the distant future.

While I might have found reading The Secret Doctrine a chore, evidently others did not, because intellectuals and political figures across the Western world were quite interested in the ideas it put forth. Roosevelt’s future vice-president, Henry A. Wallace, was a Theosophist and—back when he was Secretary of Agriculture—corresponded with exiled Russian mystic painter Nicholas Roerich. Wallace approved Roerich’s mid-’30s expedition into Inner Mongolia and Manchuria, a mission ostensibly to research drought-resistant plants but which was instead a quest for Shambhala.

Interwar Germany was a fertile ground for Theosophical ideas. Ariosophy, an offshoot of Theosophy specifically focused on combining esoteric beliefs with Germanic nationalism, was very popular. And this a good time to talk about a troublesome word: Aryan. By Blavatsky’s time, the name—which originally applied to the ancient Indo-Iranian peoples (the name “Iran” in fact derives from it)—had taken on a new, erroneous meaning. French writer Arthur de Gobineau conflated the Aryans with modern Europeans, promoting pseudohistorical beliefs about blond-haired, blue-eyed conquerors who founded every major civilization. Not helping was that many historians of that time, well into the 1950s, used the word as a synonym for “Indo-European”, which is a category that includes a wide variety of ethnic groups. It should be noted that modern Theosophists disavow any racist interpretation of their beliefs.

When the National Socialists came to power, they simultaneously promoted and suppressed occultism, depending on how useful it was to the interests of the ruling party. Heinrich Himmler took Blavatsky’s claims about the Atlantean origins of the Tibetans seriously, prompting him to send an expedition to the Himalayas in 1938. Having taken what they wanted and perhaps fearing any rivals for the worship of the State, the Nazi Party banned Theosophical societies in 1937.

Perhaps inevitably, Blavatsky’s ideas also took root in her homeland. For all their secular pretensions, the Bolsheviks were as interested in esoteric matters as the Nazis were. Theosophy was as much a part of the Russian cultural landscape in late Tsarist Russia as it had been in Weimar Germany. While the Bolsheviks banned Theosophy, along with other esoteric beliefs in 1923, there were still those among their ranks who believed they could advance the Revolution by occult means.

Alexander Barchenko, described as a “Red Merlin”, sought to combine Marxism with esoterical beliefs to create a more spiritual Communism. He found an ally in Gleb Bokii, one of the founders of the Cheka secret police and also a Theosophist. Like Roerich, they too searched for Shambhala, believing that he could fuse Buddhism with Marxist-Leninism. Shambhala and the history of those who searched for it in the early 20th century is a tangent worthy of its own post. Perhaps another time.

As a curious footnote, the notion of Hyperborea being the homeland of the ancient Russians persists in some corners of Russian ultranationalism to this day.

All of this shows that these were not merely the fringe ideas of a few marginal people, or confined to parlour discussions, but were taken seriously by prominent figures. It should come as no surprise that the authors of the time noticed this. There were writers of Science-Fiction and Fantasy who were themselves Theosophists, like Talbot Mundy and Kenneth Morris. However, since I haven’t read either author yet, I cannot not speak with any real authority on the men and their works, so for the purposes of this article, I shall confine myself to authors I have read extensively.

Of the “Three Musketeers” of Weird Tales, Clark Ashton Smith’s debt to the Theosophists is perhaps the most obvious. As Smith himself said in a letter:

“One can disregard the theosophy and make good use of the stuff about elder continents, etc. I got my own ideas about Hyperborea, Poseidonis, etc., from such sources, and then turned my imagination loose.”

Hyperborea became the setting for a number of his stories. “Poseidonis” originates, so far as I can tell, with Blavatsky, who claimed that other writers had made the error of not distinguishing between the various epochs of Atlantean history. Scott-Elliot later on laid out an elaborate timeline for Atlantis, with the continent going through a number of cataclysmic changes over the millennia. One of these was Poseidonis. The twin islands of Ruta and Daitya came later. Ruta was derived from the works of Louis Jacolliot, a French writer who did a number of Sanskrit translations. According to him, Rutas was the real source of the Atlantis myth. Like Lemuria before it, the triangular continent started off in the Indian Ocean and got relocated to the Pacific. Later theosophists folded in Ruta (minus the “s”) and subordinated it to their Atlantis-Lemuria mythology.

Ruta was later used in the mid-70s Seedbearers Trilogy by Peter Valentine Timlett, which I can tell you little about because I haven’t read any of them. And it also made a brief appearance in a 1990s storyline in Namor, The Sub-Mariner. Daitya is, so far as I can tell, not nearly as popular.

A Green Man/Thark of Mars. Art by Bernie Wrightson.

Some of Blavatsky’s statements on the earlier Root Races might sound familiar to readers of Edgar Rice Burroughs:

“There were four-armed human creatures in those early days of the male-females.”

And it’s not just echoes of the Green Martians we see here. This is what Scott-Elliot says of the Toltecs, one of the “sub-races” of the Fourth Root Race who inhabited Atlantis:

“The complexion of this race was also a red-brown, but they were redder or more copper-coloured than the Tlavatli.”

They certainly sound like the Red Martians, don’t they? Scott-Elliot also mentions “air-boats” propelled originally by “vril” and later by a force “not yet discovered by science”. Shades of the Barsoomian airships and their “eighth ray” propulsion system. Here’s what Blavatsky says early in The Secret Doctrine:

“The One Ray multiplies the smaller Rays (. . .) Through the countless Rays the Life-Ray, the One, like a thread through many beads.”

“Vril”, as an aside, is a term coined by Edward Bulwer-Lytton (immortalized in the form of the annual Bulwer-Lytton Fiction Contest) in his 1871 science-fiction novel The Coming Race. It was subsequently picked up on by occultists and science-fiction writers alike. As another aside, the Theosophical belief in ancient airships came from the flying chariots known as vimānas, found in the ancient Vedic literature of India.

Furthermore, Blavatsky describes the Third Race as “the Egg-born”. And how do the Barsoomians famously reproduce? The Black Martians are described as “the First-born”, a term used by Blavatsky. During the course of the initial Mars Trilogy by Burroughs, we learn that the sacred Valley Dor is located at the Martian South Pole, home to the “First Born”, reminiscent of the Imperishable Sacred Land and the First Root Race. It is also home to the false goddess Issus, who is revealed as a fraud at the end of The Gods of Mars. Issus Unveiled? Was Burroughs making a subtle joke? The Martian North Pole is home to a race of Yellow Martians, not unlike the Theosophical Hyperborea. Hmmm. In his Lost Continents, L. Sprague De Camp, in a chapter about the Atlantis of the occultists, observes in passing that:

“Altogether life on the Theosophical Atlantis resembles nothing so much as life on Mars as pictured in the Martian novels of Edgar Rice Burroughs.”

Barsoomian airships, which inspired the landspeeders and airships of Tatooine. Art by Jim Martin.

Fritz Leiber certainly thought so, and wrote an essay on the subject, “John Carter—Sword of Theosophy” in the September 1959 issue of the fanzine Amra, where he laid out his theory.

All this sounds very clear-cut—but it isn’t. There is no direct evidence that Burroughs read any Theosophical works. He certainly wasn’t a Theosophist himself. Leiber states that Burroughs would have been exposed to Theosophy when he lived in California. He very well might have been, but the author did not move there until some years after he wrote his early novels. Yet, as I’ve shown, it’s highly unlikely he wasn’t at least passingly aware of something that was once so widespread and influential, and the sheer volume of circumstantial evidence points to a familiarity with the subject.

Theosophy in Outline, by Frederick Milton Willis, was a Little Blue Book, part of a series of inexpensive nonfiction books on various topics which were popular at the time. We know from his letters that Robert E. Howard read LBBs so its more than likely he could have read this one. Howard’s early, unpublished Bran Mak Morn story “Men of the Shadows”, features a lengthy history lesson from wizard, an early stab at the kind of fantastical history he would later refine in his King Kull stories and “The Hyborian Age” essay, both of which freely contradict this on numerous points.

“Now, the Atlanteans were the Third Race. They were physical giants, finely made men who inhabited caves and lived by the chase.”

Howard’s footnote in the text states that the Atlanteans were Cro-Magnons, yet another idea which originated with Blavatsky. And later on in the story he mentions the “Toltecs of Lemuria”. In a letter to his friend Harold Preece, Howard weighed in on the issue of Atlantis and the sub-races:

“The occultists say that we are the fifth—I believe—great sub-race. Two unknown and unnamed races came before, then the Lemurians, then the Atlanteans, then we. They say the Atlanteans were highly developed. I doubt it.”

Howard’s conception of Atlantis varied wildly between stories, from the barbaric Atlantis of his Kull stories to the more more advanced island-continent of sorcerers which featured in the backstory of “Skull-Face”.

In the Conan story “Pool of the Black One”, Conan encounters a race of mysterious black giants on an uncharted island:

“The creatures were black and naked, made like men, but the least of them, standing upright, would have towered head and shoulders above the tall pirate. They were rangy rather than massive, but were finely formed, with no suggestion of deformity or abnormality, save as their great height was abnormal.”

Scott-Elliot talks about black giants as well—one of the sub-races of Atlantis:

“The Rmoahals were a dark race—their complexion being a sort of mahogony black. Their height in these early days was about ten or twelve feet—truly a race of giants—but through the centuries their stature gradually dwindled, as did all of the races in turn, and later on we shall find they had shrunk to the stature of the “Furfooz man”.” (“Furfooz man” is a reference to Cro-Magnon remains from Belgium, which were a recent discovery when the book was first written.)

Rmoahals were featured in the story “The Infinite Invasion” published in the September 1942 Fantastic Adventures under the Ziff-Davis house name of “E. K. Jarvis”. They also make some comic book appearances in the pages of DC’s nearly-forgotten fantasy comic Arion, Lord of Atlantis, as well as the British comic Slaine. And they’ll be appearing again later on.

In his story “The Diary of Alonzo Typer” (co-written with William Lumley), Howard Philip Lovecraft references a familiar text:

“I learned of the Book of Dzyan, whose first six chapters antedate the earth, and which was old when the lords of Venus came through space in their ships to civilise our planet.”

“Lords of Venus” refers to a belief, first promoted by Blavatsky’s successors in the Theosophical Society, Annie Besant and Charles W. Leadbeater. The Lords of the Flame came to Earth during the era of the Third Root Race to guide human evolution. It is one of the earliest expressions of the concept of “ancient astronauts”.

Lovecraft was at least casually acquainted with theosophical beliefs in the ‘20s. It should not be a surprise that the wild imagery and vast cosmic timescales Blavatsky and her followers had spoken of would appeal to someone of his inclinations. But it was not until the early ‘30s that he became interested in learning if there was any actual folklore behind it and E. Hoffman Price promised to look into the matter further.

“I am really interested in the Dzyan-Shamballah. Its cosmic purpose, the Lords of Venus, and everything in between, resonates in a special and emphatic way in my strings!”

What he learned was . . . disapppointing. Corresponding later with August Derleth, Lovecraft wrote:

“By the way—it turns out that Price’s mystical legendry was, after all, only the stuff promulgated by the theosophists—Besant, Leadbeater, &c. I thought it sounded like that. Do you know anything about the origin of that stuff? It pretends to be real folklore—at least in part (of India, I suppose)—but have a sneaking suspicion that the theosophists themselves have interpolated a lot of dope. There are things which suggest a knowledge of certain 19th century conceptions.”

Lovecraft was later loaned a copy of The Secret Doctrine from fellow Weird Tales author Henry Kuttner however there is no evidence suggesting he had time to read it before his death in 1937. What might he have written if he had? The Book of Dzyan and Lovecraft has an interesting post-script. The episode of The Real Ghostbusters, “The Collect Call of Cthulhu” (which was my first exposure to the Mythos) mentions the book in passing.

The Theosophists also went beyond lost continents and prophesied future ones as well. The continent of Pushkara is supposed to arise from the Pacific and become the home for the as-yet-to-evolve Seventh Root Race (can they really be called a “root” if they don’t exist yet?). And once again it’s Smith who took up the idea and wrote a cycle of stories around it, the decadent future continent of Zothique. In a letter to De Camp, Smith explains the origins:

“The idea for this last continent was suggested by the ‘occult’ traditions concerning Pushkara, which will allegedly become home of the 7th root race, the last race of mankind. However I doubt if the Theosophists would care for my conception, since the Zothiqueans as I have depicted them are a rather sinful and iniquitous lot, showing little sign of the spiritual evolution promised for humanity in its final cycles.”

A common theme with the Three Musketeers is that while they might have helped themselves to ideas from the Theosophists, they were in no way beholden to them. All was grist for the pulp fiction mill.

Lin Carter, as I have already mentioned on other occasions, was a man who wore his influences on his sleeve. It should not be surprising that he also borrowed ideas from the Theosophists for his first and most famous series, that of Thongor of Lemuria. Lin Carter’s Lemuria fairly teems with prehistoric critters of all kinds, from the “great graaks, the lizard-hawks of Chush” to the dwark, the “enormous and insatiable ‘jungle-dragon’ of Lemuria.” Now Carter was certainly fond of megafauna, as anyone who has read his works can attest, but in this case, Carter was merely following his source material. On dinosaurs in Lemuria, Scott-Elliot says:

“From this statement it will be seen that Lemurian man lived in the age of Reptiles and Pine Forests. The amphibious monsters and the gigantic tree-ferns of the Permian age still flourished in the warm damp climates.”

Squaring the circle, he also has antigravity airboats which are reminiscent of those of Burroughs and the Theosophical writers who (possibly) inspired him, and which originated in the Vedas of ancient India, which was the source of so much of this to begin with. Carter also uses the Rmoahals, making them a race of blue-skinned giants inhabiting eastern Lemuria. In the Appendix to Thongor At The End of Time, Carter not only name-drops Scott-Elliot when talking about the origins of the Rmoahals, but also alludes to Leiber’s theory about Burroughs. Did Leiber’s article provide the spark that led to the Thongor series, and thus the career of Lin Carter? It is certainly a possibility.

The Black Star is Carter’s one and only Atlantean novel, published in 1973 and planned as the first of a new series. It’s packed with worldbuilding details cribbed from Theosophical sources. The capital of Atlantis, Caiphul, City of the Golden Gates, is a double reference. “Caiphul” is the capital of Atlantis in the the 1905 novel A Dweller on Two Planets, by Frederick Spencer Oliver (who claimed to have channeled the whole thing from an entity known as “Phylos the Thibetan”). “City of the Golden Gates”, on the other hand, was the Atlantean capital according to Scott-Elliot. The City of the Golden Gates is also referenced in the novel The Sea Priestess by Dion Fortune, and both the DC and Marvel versions of Atlantis. The novel’s antagonist Thelatha is taken from The Secret Doctrine, the King-Demon Thevetat, of which Blavatsky states:

“It is under the evil influence of this King-Demon that the Atlantis-Race became a nation of wicked “magicians”.”

And the Lemurian airboats also put in an appearance, thus connecting not only with the theosophists, but with the original Indian Vedas. Once again, Carter’s own notes at the end of the novel freely admit the borrowings, adding:

“ “Phylos” by the way, is hardly in any position to accuse me of literary theft, since he himself states in the most positive of terms that his book is not fiction but historical fact—and historical data, of course, can hardly be copyrighted by him or by anybody, since nobody invented it.”

Which I suppose sums up the attitude of many of these writers.

Now consider all the creators influenced by these authors, and you begin to see just how broad the influence of Theosophy has been on our popular culture. Now, a deep understanding of where tropes originate isn’t necessary for enjoying these works, far from it. But knowing where these threads came from can give one an appreciation for the greater context.

Pay close enough attention, and you might see some of those threads yourself.