A. Merritt and The Ship of Ishtar

The mighty A. Merritt.

The anniversary of A. Merritt's death was a few days ago. His mighty influence still echoes and resonates nine decades after his death. One big reason for that is his ground-breaking novel, The Ship of Ishtar. In its day, Merritt’s novel surpassed in popularity competitors like A Princess of Mars and Tarzan of the Apes. An adventure of mythic scope and borderline Sword-and-Sorcery, The Ship of Ishtar has captivated generations of exotic adventure fans. We are approaching the centennial of its initial publication very rapidly.

The Ship of Ishtar was first serialized in Argosy All-Story in November 1924. It was immediately a huge hit with Argosy's readership. Not since the days of "The Moon Pool" had there been such a furor amongst the Argosy audience--and part of that previous buzz was due to Merritt writing his novella as if it was factual. The Ship of Ishtar was an obvious work of fantasy and its esteem among fantasy fans only grew over the next two decades.

As pulp mega-scholar/collector, Doug Ellis, put it earlier this year:

"In 1938, when the editors of Argosy took a survey of their readers to determine the most popular story they’d ever published, The Ship of Ishtar took first place, relegating Edgar Rice Burroughs’ Tarzan of the Apes to the runner-up position."

There you have it. Among American fantasy fans, The Ship of Ishtar reigned supreme as the fantasy novel for a solid four decades, only to be usurped by the current heavyweight champion, The Lord of the Rings.

The Ship of Ishtar was my personal gateway to Merritt's works. I have written--and podcasted--about it several times. If you're curious, check out the links below:

Forefathers of Sword and Sorcery: A. Merritt — DMR Books

My podcast looking at The Ship of Ishtar:

https://archive.org/details/dialpforpulp/dialpforpulp-009-Oct08.mp3

https://archive.org/details/dialpforpulp/dialpforpulp-010-Dec08.mp3

https://archive.org/details/dialpforpulp/dialpforpulp-011-Dec09.mp3

Today, I'm going to look at the influence The Ship of Ishtar exerted upon several Sword-and-Sorcery tales (and one S&S-adjacent novel). Before I do that, I want to repost my list of authors who were/are fans and admirers of A. Merritt:

Merritt's reach was vast. Robert E. Howard, Lovecraft, Clark Ashton Smith, Max Brand/Frederick Faust, Arthur Leo Zagat, Edmond Hamilton, August Derleth, CL Moore, Jack Williamson, Leah Bodine Drake, Lloyd Arthur Eshbach, RH Barlow, Hugo Gernsback, E.E. "Doc" Smith, A.E. van Vogt, Leigh Brackett, Robert Bloch, Poul Anderson, Ray Bradbury, Andre Norton, Donald A. Wollheim, Gardner F. Fox, Henry Kuttner, Sam Moskowitz, Julius Schwartz, A. Bertram Chandler, Lester Del Rey, James Gunn, Frederik Pohl, Algis Budrys -- all admired him.

The same can be said for newer authors like Moorcock, Mike Resnick, Barry N. Malzberg, Lin Carter, Robert Silverberg, Ray Capella, Brian Stableford, Anne McCaffrey, Stephen King, Karl Edward Wagner, Fred Chappell, CJ Cherryh, Brian Lumley, James Cawthorn, Robert Weinberg, Gary Gygax, Ben P. Indick, Sheri S. Tepper, Keith Taylor, Robin McKinley, Marvin Kaye, Baird Searles, Ardath Mayhar, Gardner Dozois, Eileen Kernaghan, Piers Anthony, Stephen Hickman, Ed Gorman, Orson Scott Card, SM Stirling, Tim Powers, Raymond E. Feist, Elizabeth Hand, Frank Lauria, Cory Panshin, Douglas Preston, John C. Wright, Paul di Filippo, Charles R. Rutledge, John C. Hocking, Adrian Cole, Dave Hardy, John C. Tibbetts, Steve Rasnic Tem, Ryan Harvey, Christopher Chupik, Keith West, Fraser Sherman, JD Cowan, William Meikle, John E. Boyle, Brian Niemeier, Jay Barnson, Aonghus Fallon, Daniel B. Davis, Ken Lizzi and D.M. Ritzlin.

Not too shabby. Certain authors might've held some other Merritt novel higher than The Ship of Ishtar, but I've never read where any of them bad-mouthed it. For forty years, The Ship of Ishtar was the American fantasy novel.

I'll start with Robert E. Howard. As with Edgar Rice Burroughs, REH was cagey about his admiration for Merritt. He called Merritt "great" one time that we know of. Burroughs never even got that much, but we know that Howard had more ERB books in his personal library than those of any other author---that includes REH's personal literary idol, Jack London.

By the same token, Howard seems to have kept a close eye on Merritt, who had supplanted ERB as the top author in the "imaginative fiction" field by the early 1920s. The Ship of Ishtar was published in Argosy in 1924 and in hardcover in 1926. Did Merritt's novel of adventure set in an ahistorical fantasy world influence Howard?

1926 is the year when REH began writing "The Shadow Kingdom". Later Kull yarns would mention that Kull was an escaped galley slave. John Kenton in 'Ishtar' was one as well. There is, at times, a sort of dream-like aspect to The Ship of Ishtar that is also found in the Kull stories.

At some point in 1928, Robert E. Howard had written "Skull-Face", one of his more famous yarns and which put him on the map with Lovecraft, among others. While I think that Rohmer and HPL--along with another Merritt novel--had more influence upon "Skull-Face", I find Costigan's and Kenton's intense desires to "escape the modern world" quite similar. Both are World War One veterans who have given up on the modern world in their own ways. Both of them then go on to fight towering sorcerers who threaten their lady-loves.

In 1930--perhaps slightly earlier--Robert E. Howard created his Cormac Mac Art character; an Irish pirate during the Dark Ages. Cormac's close comrade through several adventures is a Viking, Wulfhere. Cormac's nickname is "The Wolf". In The Ship of Ishtar, John Kenton, a light-eyed, black-haired Irishman like Cormac, is nicknamed "The Wolf" by his Viking brother-in-arms, Sigurd. I think Kenton and Sigurd were not only models for Cormac and Wulfhere, but were also the template for REH's Turlogh O’Brien and Athelstane.

Robert E. Howard also wrote "The Voice of El-lil" in 1930. In that yarn--which none other than Glenn Lord declared to be "Merrittesque"--Howard stated that the Sumerian civilization was "six thousand years old". That was a solid millennium older than the academic consensus at the time, but it matches up nicely with the same date given by Merritt in The Ship of Ishtar.

In 1932--but maybe earlier--Robert E. Howard wrote "The Shadow of the Vulture". That is the yarn which introduced the iconic Red Sonya of Rogatino to the world. Sonya is verbally quite brutal to Otto von Kalmbach in the first half of the story, which is quite similar to how the red-headed Sharane treats Kenton for the first half of The Ship of Ishtar. Sonya is also dissimilar--in this particular way--from almost any earlier Howardian heroine up to that point.

By 1932, Howard had been playing with various elements from The Ship of Ishtar for at least six years. While Merritt's Dweller in the Mirage very likely have kicked off REH's newest, Conanic phase, there was still gas in the 'Ishtar' tank. One of the most beloved Conan yarns, "Queen of the Black Coast", was the result.

In The Ship of Ishtar, John Kenton is a traumatized veteran of World War One. He desperately wants to escape the insanities of the modern world. When given the opportunity to come aboard the Ship of Ishtar, Kenton seizes the chance. He is now in an Otherworld like nothing he has ever known before.

Compare that to Conan in "Queen of the Black Coast". Fleeing the civilized idiocracy of Messantia, Conan leaps aboard the Argus, which ship takes him far away from anything he has ever known.

Kenton leads a galley-slave revolt and wins the love of Sharane, an archeress and high priestess of Ishtar. She has remained virginal for the entire time she has been confined to the Ship. Sharane leads a posse of Ishtarian slay-queens, all of whom wield bows.

In QotBC, Conan is attacked by Belit and her pirates. Belit is an archeress--in fact, that appears to be her only combat skill. She gives herself--as a virgin--to Conan. Belit then reveals her encyclopaedic knowledge of the Shemitic religion, with a special emphasis on Ishtar.

I don't want to reveal major spoilers at this point, so I'll end this about midway through the novel. Kenton has infiltrated the sorcerer-city of Emakhtila. He is able to covertly observe Narada, a priestess-dancer of Bel. Meanwhile, Zubran--a lusty and cynical Persian from the time of Cyrus--has a ring-side seat.

"She [Sharane] was a princess, they say," the woman spoke. "They say she was a princess in Babylon."

(...)

"And Narada—the God's Dancer—loves the Priest of Bel!"

“The sable silken strands had meshed a woman [Narada], a woman so lovely that for a heartbeat Kenton forgot Sharane. Dark she was, with the velvety darkness of the midsummer night; her eyes were pools of midnight skies in which shone no stars; her hair was mists of tempests snared in nets of silken gold. Sullen indeed was that gold, and in all of her something sullen that menaced the more because of its sweetness.”

(...)

Narada prepares to dance like a desert whirlwind, like a quenchless flame. Art by Virgil Finlay.

“Narada arose, abruptly. Her handmaids bent over drums and harps; set their pipes to lips. A soft and amorous theme beat up from them (…)

Louder the music sounded; quicker, throbbing with all love longing, laden with all passion; hot as the simoon [a desert storm/whirlwind]. To it, as though her body drank in each calling, imperious note, turned it into motion, made it articulate in flesh, Narada began to dance.”

(...)

Maddening, breathless, grew dance and music, and in music and dance Kenton watched mating stars, embracing suns, moons swollen with birth. Gathered in them he sensed all passion, all desire of all women under stars and suns and moons...

The music slowed, softened; the dancer was still; from all the multitude a soft sighing arose. He heard Zubran, his voice hoarse:

"Who is that dancer? She is like a flame! She is like the flame that dances before Ormuzd on the Altar of Ten Thousand Sacrifices!"

(...)

The blood hammered hot in Kenton's veins—"She dances the surrender of Ishtar to Bell" It was the Assyrian, gloating

(...)

"Aie!" [Zubran] cried. "Cyrus would have given fifty talents of gold for her! She is a flame!" cried Zubran, and his voice was thick, clogged. "And if she is Bel's—why then does she look so upon the priest?"

None heard him in the roaring of the multitude; soldiers and worshipers, none of them had eyes or ears for anything but the dancer.

(...)

The youth twisted, sprang upon his feet, faced the priestess.

"Ishtar!" he cried. "Show me your face. Then let me die!"

Compare this to a similar scene in "Queen of the Black Coast”. In this case, Belit is seducing Conan--who until moments before was a mortal enemy. In The Ship of Ishtar, Narada is also crossing forbidden lines by attempting to seduce the High Priest of Bel rather than worshipping Bel himself. As a final aside, we also have the obvious connection betwixt "Bel" and "Belit". We know that Howard started with "Tomyris"--the name of a queen who fought the Babylonians--but he decided on "Belit" instead.

Belit doing her mating-dance on the Tigress. Art by Stephen Fabian.

"She [Belit] was slender, yet formed like a goddess: at once lithe and voluptuous. Her only garment was a broad silken girdle. Her white ivory limbs and the ivory globes of her breasts drove a beat of fierce passion through the Cimmerian’s pulse, even in the panting fury of battle. Her rich black hair, black as a Stygian night, fell in rippling burnished clusters down her supple back. (...)

"As they moved out over the glassy blue deep, Bêlit came to the poop. Her eyes were burning like those of a she-panther in the dark as she tore off her ornaments, her sandals and her silken girdle and cast them at his feet. Rising on tiptoe, arms stretched upward, a quivering line of naked white, she cried to the desperate horde: 'Wolves of the blue sea, behold ye now the dance—the mating-dance of Bêlit, whose fathers were kings of Askalon!'

And she danced, like the spin of a desert whirlwind, like the leaping of a quenchless flame, like the urge of creation and the urge of death. Her white feet spurned the blood-stained deck and dying men forgot death as they gazed frozen at her. Then, as the white stars glimmered through the blue velvet dusk, making her whirling body a blur of ivory fire, with a wild cry she threw herself at Conan’s feet, and the blind flood of the Cimmerian’s desire swept all else away as he crushed her panting form against the black plates of his corseleted breast."

Belit was barely clothed more than Narada, if at all. We learn later that she seems to have a special relationship with Ishtar. Merritt likens Narada to a 'simoon' and REH likens Belit to a synonymous 'desert whirlwind'. Being a denizen/queen of the Black Coast, Belit has no obvious connection to the 'desert'--she is far more a part of the jungle and the sea. Yet, Howard uses almost identical language to describe Belit as Merritt did with Narada. In addition, just as Sharane is said to have been a 'princess in Babylon', Belit proclaims herself a daughter of kings in Askalon. I should note that Howard is obviously conflating Sharane and Narada. A good move, story-wise.

Meanwhile, we see Merritt describing Narada's dance as "mating stars, embracing suns". REH describes Belit's mating-dance as "the white stars glimmered through the blue velvet dusk". In addition, we have, "Gathered in them he sensed all passion, all desire of all women under stars and suns and moons..." That isn't too far from "And she danced (...) like the urge of creation and the urge of death."

We also have "And she [Belit] danced (...) like the leaping of a quenchless flame..."

From The Ship of Ishtar:

The music slowed, softened; the dancer was still; from all the multitude a soft sighing arose. He heard Zubran, his voice hoarse:

"Who is that dancer? She is like a flame! She is like the flame that dances before Ormuzd on the Altar of Ten Thousand Sacrifices!"

(...)

"Aie!" [Zubran] cried. "Cyrus would have given fifty talents of gold for her! She is a flame!" cried Zubran, and his voice was thick, clogged. "And if she is Bel's—why then does she look so upon the priest?"

For the record, the altars of Ormuzd, the deity of the Zoroastrian religion, feature an 'eternal flame'. In other words, a "quenchless flame".

Finally, we have this:

"Her [Belit's] white feet spurned the blood-stained deck and dying men forgot death as they gazed frozen at her."

From Merritt:

None heard him [Zubran] in the roaring of the multitude; soldiers and worshipers, none of them had eyes or ears for anything but the dancer [Narada].

(...)

The youth twisted, sprang upon his feet, faced the priestess [Sharane].

"Ishtar!" he cried. "Show me your face. Then let me die!"

Here we have one example of Narada mesmerizing a throng of spectators and then Sharane driving a young man insane just to see her face.

There are actually a couple more minor parallels I find interesting, but I'll leave those for another day. To sum it up, Robert E. Howard obviously borrowed various elements, concepts and phrases from The Ship of Ishtar, but he made them his own.

Sharane looking very much like Jirel.

Around the same time as REH was writing "Queen of the Black Coast", Catherine "C.L." Moore was crafting her first tale of Jirel of Joiry. Jirel was a red-haired noblewoman commanding a castle in medieval France. I have asserted many times that Moore--a big Merritt fan--was inspired primarily by the red-headed Lur the Wolf-Witch in Dwellers in the Mirage. That said, I do see elements of Sharane in Jirel's personality. Very likely, Moore had a character vaguely similar to Sharane in mind and then she read Dwellers in the Mirage, at which point everything fell into place. One thing is for certain: both Sharane and Lur were both bad-ass redheads with a weakness for bad boys, just like Jirel.

Meanwhile, Henry Kuttner was in the process of developing his 'Elak of Atlantis' series. There are Merrittesque elements in all of them, but "Dragon Moon" is easily the most Merritt-influenced of all the Elak tales.

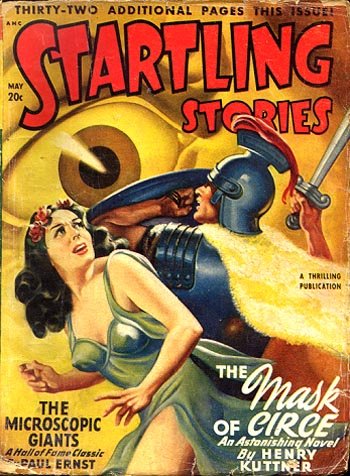

Moore and Kuttner eventually got married, becoming the first "power couple" in SFF. Growing up in the 1920s, both were die-hard Merritt fans. They made their Merritt fandom explicit in 1948, when they wrote The Mask of Circe. That novel is a blatant homage to The Ship of Ishtar, switching out Mesopotamian mythology for that of the Greeks.

Hot on the heels of the Kuttner-Moore power couple were their slightly younger compatriots, Edmond Hamilton and Leigh Brackett. Hamilton would write numerous Merrittesque tales over the years--many of which have been collected by DMR Books here and here. However, Brackett's "Sea-Kings of Mars", later novelized as The Sword of Rhiannon, is the most obvious tribute to The Ship of Ishtar that either of them ever wrote.

You can find my review of it here. However, fifteen years on, I have a few more things to say about it, at least when it comes to The Ship of Ishtar. The relationship between Carse and Ywain is definitely based upon Kenton and Sharane. Kenton is an archaeologist and Carse is a 'defrocked' archaeologist. Ywain mocks and love/hates Carse just like Sharane does Kenton. Carse leads a galley-slave revolt, just like Kenton. Boghaz, the Martian thief, fills a similar role to Gigi in The Ship of Ishtar. The big "script flip" is that, in 'Ishtar', half the ship belongs to the priests of Nergal, with the death-god's altar in the stern. In 'Rhiannon', Ywain--analogous to Sharane--houses one of the inhuman Dhuvians in her captain's cabin.

To wrap all this up, I'll look at a more recent Sword-and-Sorcery scribe: namely Michael Moorcock. We know he and James Cawthorn were Merritt fans. They ranked The Ship of Ishtar among the hundred best in Fantasy: The 100 Best Books. Where we see the influence is in the first two Elric novels. In Elric of Melnibone, we encounter The Ship Which Sails Over Land and Sea. Built cooperatively between the sea-god, Straasha, and Lord Grome, god of growing things, the Ship is contested between the two deities by the time Elric wants it. This is similar to how the Ship of Ishtar is divided across its middle between the warring forces of Ishtar and Nergal. Moorcock has always been fond of putting a twist on his influences.

Lord Grome and the Ship Which Sails Over Land and Sea. Art by Frank Brunner.

The second Elric novel, Sailor on the Seas of Fate, presents another twist on Merritt's 'Ishtar' template. In this case, Moorcock plays with the concept of the Ship landing at sundry ports and taking on passengers/crew-members from various time-periods, all the while sailing the seas in a sort of limbo. Moorcock expands on this by making the "sea" the Ship sails on multiversal as well as multi-temporal. He certainly got some mileage from that idea and Merritt led the way with it. All praise to Moorcock for doing so.

Michael Whelan's painting for Sailor on the Seas of Fate.

Well, that wraps up my look at the half-century of profound, epic influence that The Ship of Ishtar exerted upon various works of heroic fantasy and sword-and-planet. DMR Books will be publishing a landmark centennial edition of Merritt's immortal novel this fall. I'll have more to say then.