Wisdom from an Angry God: A Rebuttal to Peter Bebergal's Appendix N

Published in 2017 but, really started several years earlier, was Jeffro Johnson’s book Appendix N: The Literary History of Dungeons & Dragons. The prep work that went into this book earned Johnson a best fan writer Hugo nomination. At the time, Johnson’s Appendix N was the only in-depth exploration of how the works listed in Appendix N of the Dungeon Masters Guide related to the development of D&D. It remains the only such work. Now comes along a book with a suspiciously similar title, Peter Bebergal’s Appendix N: The Eldritch Roots of Dungeons and Dragons.

Both titles seemingly refer to the Appendix N found in the 1979 Dungeon Masters Guide written by E. Gary Gygax. The actual Appendix N contains a list of fictional works that Gygax cites as inspiration in “…all of the fantasy work I have done…” by which he means his work on Dungeons and Dragons and role-playing games in general.

At the time Johnson’s book was released I thought an anthology of Appendix N works would be a nice companion piece to read alongside Johnson’s book – for the new generations now discovering D&D (or sadly, through its rather wan and misguided current editions). I hoped that Johnson’s book would help enlighten new players and a companion book would further assist. Peter Bebergal’s bizarre Appendix N is such an attempt. And presumably it could leave the door open for others to make Appendix N anthologies out of brony and animé fan fiction. The works Gygax listed in Appendix N is simply too large, too deep, and too varied to be contained in a single anthology, considering that most works listed are full-length novels.

Bebergal’s preface goes wrong, straightaway, adopting a light but constant condescension to his subject and his readers. “In the early 1970s, the young [emphasis mine] game designer and wargame aficionado Gary Gygax had the idea to add fantasy elements to medieval wargaming, developing a system called Chainmail, the 1971 precursor to what would become Dungeons & Dragons.” Gygax was already in his early 30s when Chainmail was published; he was in his late 30s when the first booklets of Dungeons and Dragons appeared in 1974. Gygax was well into adulthood and rapidly approaching middle age.

“It was a DIY endeavor, “ Bebergal continues, “with a punk sensibility, an ethos that was not constrained by any preconceived ideas, expectations, or bottom lines. Gygax and company were able to take risks and fill in the details in whatever way they wanted, contrary to current gaming protocols.” There isn’t the slightest connection to punk music in D&D’s conception. “Punk” is just a word Bebergal throws around, and doing so elides sensibility in the wargaming community which predates punk by at least thirty years (perhaps centuries) and even persists today. Gaming, at its core, is a hobby which seeks neither mediation or approval from Johnny-come-latelies.

If one were to (wrongheadedly) feel compelled to connect D&D to a do-it-yourself sensibility of the time, a stronger case would be to the 1960s countercultural movements – to the spirit that compelled hippie communes, the Whole Earth Catalog, and even the EST movement. And you’d still be wrong. “Not constrained by preconceived ideas”? Only if you want to maintain that the books Gygax listed as being influential were, somehow, not influential at all. Gygax’s Appendix N is an explicit list of preconceived ideas he was trying to emulate. “Current gaming protocols?” Umm, what? There are gaming protocols? Where? Last I heard, anyone can still freely create any game to play any way they want. Why all the bad faith? Bebergal is loose with fact and history. His thinking issues from a position where this sort of control over gaming and literature exists or, worse, is considered desirable. This book is an attempt to get ahead of forthcoming product and rules changes in the game from WOTC. It is a mediocre attempt at retconning a hobby at its source. Bebergal’s thesis is so off-base as to make one’s jaw drop that it must be quoted in full:

“What Appendix N is not, however, is a map to D&D rules, monsters, or gameplay. In fact, some of Gygax’s sources seem puzzling, such as the traditional science fiction adventures of Stanely Weinbaum and Frederic Brown. It is, however [sic], a full list of the works Gygax cites as inspirations. Moreover, while none are mentioned by name, Gygax points out that horror movies, comic books. and fairy tales also occupy rooms in the fast dungeon of his imagination. Gygax’s Appendix N is also not the last word on literature and D&D. In the 1981 edition of the Basic D&D set, editor Tom Moldvay included an ‘Inspirational Source Material,’ his own list of what he describes as ‘useful’ to ‘improve a dungeon, flesh out a scenario, and provide inspiration for a campaign.’”

So, I guess Appendix N is just whatever anyone says it is? Well, no. Just no. The list may not be a complete map, but Johnson's book has quite solidly shown how many of the things included in the works of Appendix N map to things included in D&D and AD&D. “No map to rules, monsters, and gameplay?” It beggars belief. Let’s not even get into the tautology, “It is, however, a full list of the works Gygax cites as inspirations.” Yes, the list is indeed the list. Bebergal immediately contradicts himself, pointing out that Gygax said in Appendix N that it was not a “full” list. Nonetheless, as Johnson demonstrates at length, there are clear connections in AD&D to rules, monsters, and gameplay. To then go on to say Gygax’s list is merely an offering of “…a selection of what shaped his youthful interest…” and that Moldvay’s own list of inspirational works contained in the basic D&D book as offering “…what players might look to for gaming stimulation…” is an odd claim to make, especially as Moldvay’s list substantially overlaps with Gygax’s own. Lastly, if the presence of Weinbaum and Brown is confusing to you, perhaps you haven’t thought about it enough. Let me suggest that Jeffro Johnson’s Appendix N may provide some elucidation.

Bebergal mentions the connections of Moorcock to the alignment system, Vance to the magic system, Lovecraft to many monsters, yet he also writes “no map to rules, monsters, and gameplay”. But then again we live in an age of fiery, violent, and peaceful protests. Bebergal’s book is for entryists with a desire to refashion gaming to their novice interest. Anyone with a passing familiarity with the genre can make the connections: orcs from Tolkien, white apes from Burroughs, displacer beasts from A.E. van Vogt. Oh, van Vogt. He’s not in Appendix N? He’s one of those unlisted inspirations that Gygax mentions. Appendix N is not peripheral to Dungeons and Dragons – it’s the core. As such, entryists like Bebergal seek to control with the mediocre wizardry of revisionism.

I’m not sure how Bebergal distinguishes between rules and game play. He never says. But, as to rules, I offer one example. Bear with me – this gets a little lengthy. It is important as an illustration of the depth of connections between the works in Appendix N and the rules as presented by Gygax in AD&D.

Take Poul Anderson’s novel The Broken Sword. Being a novel, it could not appear in Bebergal’s book. Another Anderson story does appear within the pages – The Tale of Hauk. Both tales are some of Anderson’s finest work and they share superficial similarities. Both are set in the dark age/early medieval Viking period. They present Norse culture in a similar manner. Tale of Hauk has no direct connection to specific rules as presented in AD&D. The Broken Sword connects to the AD&D rules about as deep as you want to go.

The Broken Sword is a dark story set in the Danelaw. Orm, a successful Viking, settles down in the Danelaw with his Christian wife. To mollify her Orm converts to Christianity. Later he repudiates the religion and refuses baptism to his infant son, opening the door for the elf, Imric. Imric steals the infant and replaces it with a troll-born changeling. The human infant is raised by the elves and named Skafloc while the changeling is named Valgard and is raised by humans. The two sort-of siblings come into conflict and the very dark tale rolls on from there. It should be noted that Anderson’s trolls are more akin to Tolkien orcs than the regenerating trolls of AD&D. The map isn’t a one-to-one use of terms, this isn’t some sort of licensed adaption. It is deeper than that. Let me walk you through it.

The influence Anderson had on Gygax has to do with the Cleric character class. The events of The Broken Sword would not have occurred had the priest been allowed to baptize Skafloc. In The Broken Sword the Christian faith is transcendent and in the process of replacing the forces of fairy and indeed all prior mythologies. It’s been said that clerics are not well represented among the works of Appendix N or pulp fiction in general but, while they may be underrepresented as protagonists there are plenty of clerics and other religious characters in pulp fiction. In AD&D Cleric spells are doled out differently than the Vancian magic wizards memorize from books. Clerical spells come from the deities themselves. Clerical spells are fragments of heaven brought to earth. Page 38 of the Dungeon Masters Guide lays it out: first and second level clerical spells are available due to the background (rites) of their church; third through fifth level spells are bestowed upon a cleric through the “supernatural servants'' of the cleric’s deity; sixth level and greater spells are bestowed upon a cleric by the god itself.

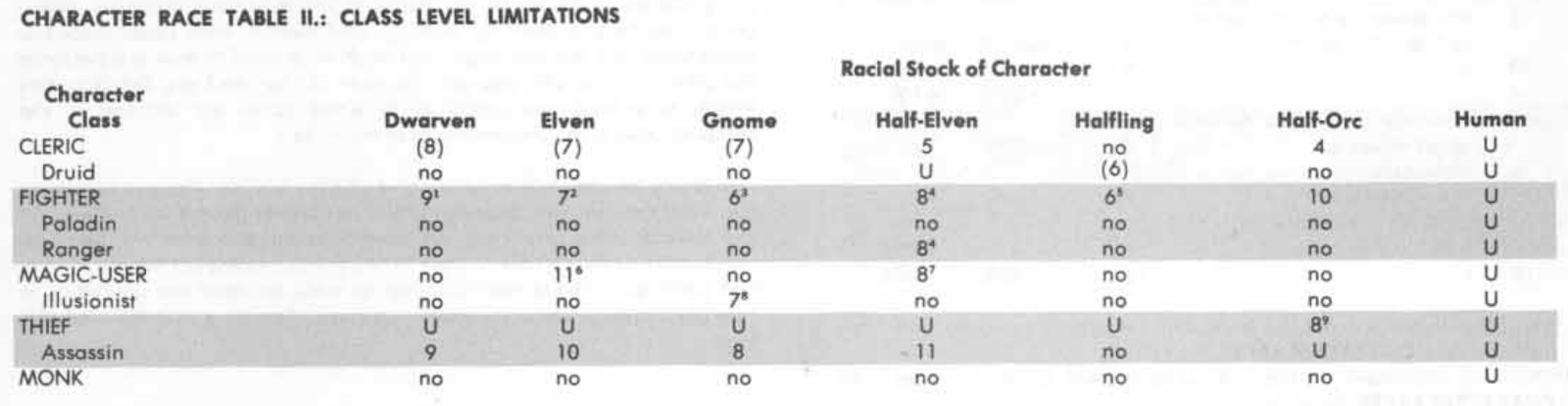

Now look at the Players Handbook, page 20. The table there shows spells usable by clerics becoming available by character level: third level spells become available to clerics of fifth level and greater; fourth level spells at seventh and eighth level; sixth level spells become available to clerics of eleventh level or greater and only if they have a 17 wisdom.

Finally, look at The Players Handbook, page 14, Class Level Limitations by race. The pertinence of this table has been the biggest bone of contention in AD&D over the years. Some see it as a ham-handed means of mitigating the advantages the various non-human races gain. But what if we gave Gygax his due? What if we took cues from the fiction to try and get behind his design, something Bebergal dares not undertake. The half-orc cleric is limited to fourth level not because their bonuses to strength and constitution are so awesome. This isn’t about play-balance. It’s because fourth level restricts half-orcs to just first and second level spells – the servitors of the gods (i.e. angels) will have nothing to do with them! Half-orcs are supernaturally unclean. Half-orcs can learn the rites of their church but their spiritual corruption puts them beyond the pale. Half-elves fare little better. Half-elf clerics are allowed fifth level which puts their foot in the door to third level spells but, no greater.

In The Broken Sword both Skafloc and Valgard can use minor spells in the book but no great magics.

In AD&D terms, Skafloc is a half-elf; Valgard a half-orc. Note this is by the cultures they were raised in. It isn’t as simplistic as genetics (does genetics even mean anything in a fantasy story? Should it?) Valgard is raised among humans and has human culture but troll blood. Skafloc is raised among elves and has elven culture but human blood. So, it’s a sensitive exploration of the effects of cross-cultural child-rearing on diversity? Yes. And no. Our modern reader may be shocked by Anderson’s conclusion of this scenario, but I will let you read it yourself. Both Skafloc and Valgard are limited by their racial stock.

So it goes down the line. Halflings (not an Anderson thing, but Tolkien) are allowed no magic at all of whatever sort. Gnomes and Elves are limited to seventh level and thus a maximum of one fourth level spell. Dwarves with a maximum of eighth level get a maximum of two fourth level spells. The servitors of the deities will interact with elves, dwarves, and gnomes but, only barely. All the supernatural races are prohibited from direct interaction with their deity if they have one at all. Plus, players are forbidden from playing dwarven, elfin, and gnome clerics – that’s what the parentheses in the table means. You can play Skafloc and Valgard but the higher level magics of Imric are forbidden to player elves, gnomes and dwarves.

Why would their gods deny them? Because the fairy are of the earth, not the heavens. Anderson depicts the fairy as being in direct opposition to Christianity and as being supplanted by Christianity. Even though AD&D does allow for non-human gods, the rules in the Players Handbook and Dungeon Masters Guide are the most consistent with a Christian (and human) deity that is superior to that of the other fairy mythos just as depicted in The Broken Sword. Indeed, the clerical spell lists are chock full of rather biblical effects. Why for example, would a priest of Nergal need a healing spell? Is healing the ethos of Nergal? Ideally, each deity would have a tailored list of spells unique to their faith. I reckon both the Players Handbook and Deities and Demigods only had so much space available. Gygax did expect some do-it-yourself. The Dungeon Masters Guide makes it clear that there is a method available for both players and dungeon masters to create their own sets of spells tailored to their needs.

That is a lot of words to say that the elves and orcs in AD&D most closely match that of Anderson’s elves and trolls. But, even more compelling is that the relationship of the fairy creatures of AD&D to the heavens most closely matches that of Anderson’s The Broken Sword. These are not Tolkien’s near angelic elves. These are amoral creatures of superstition, their presence most often does not bode well and are suspicious to the gods themselves (as shown by the rules). At best they are tricksters and at worst they are perverse and evil. No wonder the gods and their servitors don’t trust them. They are Rumpelstiltskin, not Elrond. They are symbolic representations of the earthly things: fire, forests, water, storm. The fairy are not creatures of heaven. It takes looking at and internalizing multiple parts of multiple books. Gygax doesn’t just lay out the conceit but it is there in the game’s bones.

So, no map to D&D rules? It’s baked right into the core of AD&D at multiple levels. This is but one example. Johnson’s book pulls on the threads of many more. Bebergal makes assertions convenient to his ideological objectives, but offers no proof. There are so many more things that could be criticized -- C.L. Moore is included because Bebergal ostensibly wants to hold up Jirel of Joiry as an example of a female character. But he presents no evidence that Gygax read Moore, merely speculates that it’s likely that he had. This is no knock on Moore. The Jirel stories are good fine stories but, despite their quality they offer no insight on the development of Dungeons and Dragons. There are plenty of female characters within Appendix N. Looking at just the Robert E. Howard Conan stories we have both Belit and Valeria. If one must look outside the Appendix N list Howard also has Dark Agnes de Chastillon who has both buckles and swashes.

Tale of Hauk does not include this relationship between fairy and Christianity. Yes, it’s a Viking tale but, the relationship between a fading fairy world and a transcendent upsurge of Christianity is absent. It makes one question whether its lack of Christian content was a deliberate choice. We are also living in a time of an ascendant ideology attempting to replace others. The similarity of titles and direct (though ham-handed) refutation of Johnson’s thesis would seem to imply a similar replacement.

Finally, the afterward by Ann VanderMeer. Really, the less said the better. She may rely on the authority of wearing the masthead of Weird Tales like a skinsuit for a few years in the early 2000s but it cuts no ice with me. She asks the pressing question nobody else dares ask: “What if gnolls were nonbinary?” Would the two seconds of not thinking about a gnoll’s gender before my fighting-man puts them to the sword count as a hate crime? Similarly, she asks what if the necromancers in Clark Ashton Smith’s story were partners? Her cats must be withholding affection from her. An astute reader might throw his hands up and ask “What if Clark Ashton Smith was actually included in Appendix N?” Was their sex life relevant to the story? No? Well, who cares? And, what is the connection to Dungeons and Dragons which always featured the ability to play a character of any gender and sexual orientation? VanderMeer’s afterward offers no particular insight despite her credentialism, and social justice entryism.

Notwithstanding Bebergal and VanderMeer’s critical framing, is it a bad collection? No, it’s a fine anthology with many good stories. All of which can be found elsewhere and in better company. The book is simply not that reflective of the actual Appendix N. As Bebergal says, “…the book you are holding is my own Appendix N…” Which is accurate. Perhaps the title should have been, “My Appendix N”? Don’t bronies have their favorite stories, too? What about the bronies, dude? My point is nobody cares about Bebergal’s Appendix N. He didn’t design the most popular role-playing game. He only shows up to confirm his own lazy biases rather than take in the true merit of Gygax’s list. Exploring what was compelling about a Gygaxian world is worth doing because it has inspired nearly two generations of readers and gamers.

So give Bebergal’s book a pass. Go big instead. Put your time and money into reading the works of Appendix N (find the old editions), the Players Handbook, Monster Manual, and Dungeon Masters Guide. Form your own conclusions. Jeffro Johnson’s Appendix N is far better company on this adventure. Johnson shows there is more treasure to bring up from his passionate, engaging delve. What could be more “punk” and “DIY” than that? Bebergal, though, just stumbles into the first pit trap on level one. He needs to roll a new character, hope for a better wisdom stat, and try a whole lot harder. The Tale of Hauk does include this tidbit, a quote from Odin:

Kine Die, kinfolk die,

and so at last oneself

This I know that never dies:

how dead men’s deeds are deemed

These words Anderson has taken from the Hávamál, the words of Odin in the Poetic Edda. We know Bebergal has read them. Perhaps he might think about how they might apply to himself? It is, after all, wisdom from a god.