Rangers

Somewhere in the wild country just across the river lies an enemy. An enemy poised to attack the settlements and villages of the people you are sworn to protect. Your job, your mission, your calling, is to patrol this dark border, to warn your people of impending attack, to interdict raiding parties bent on mayhem, or to penetrate that wilderness country and strike your enemy in his home country in an effort to eliminate the threat all together.

You are a Ranger.

The figure of the Ranger is archetypal across centuries of history. From medieval yeoman foresters, patrolling the king’s forest to protect vert and venison, to colonial American forces tasked with defending settlements and raiding the enemy, to official elite units of the U.S. Army tasked with direct-action operations, raids, personnel and equipment recovery, and light-infantry operations.

The Ranger is also an archetype of mythic tales. The Ranger forms a distinctive class in role-playing games, and even a cursory look at the LARP world kicks up whole companies of hooded and cloaked men and women, armed with bow and sword.

There is something profoundly appealing about the image of both the historical and the mythic Ranger as a wanderer of the wild lands; as a stealthy combatant flitting through the forest like a shadow; as a stalwart-but-seldom-seen defender of the hearth and home of the small folk.

Our conception of the Ranger of the mythic realm can be traced to a singular character: Aragorn, son of Arathorn, known as Strider. He was memorably introduced in J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings as he sat quietly with a pipe and a tankard in a corner of The Prancing Pony:

“Suddenly Frodo noticed that a strange-looking weather-beaten man, sitting in the shadows near the wall, was also listening intently to the hobbit-talk. He had a tall tankard in front of him, and was smoking a long-stemmed pipe curiously carved. His legs were stretched out before him, showing high boots of supple leather that fitted him well, but had seen much wear and were now caked with mud. A travel-stained cloak of heavy dark-green cloth was drawn close about him, and in spite of the heat of the room he wore a hood that overshadowed his face; but the gleam of his eyes could be seen as he watched the hobbits… As Frodo drew near he threw back his hood, showing a shaggy head of dark hair flecked with grey, and in a pale stern face a pair of keen grey eyes.”

This mysterious stranger was one of a tribe of Rangers, the Dunedain of the North, descendants of lost kings, versed in the lore of the wilderness.

“…In the wild lands beyond Bree there were mysterious wanderers. The Bree-folk called them Rangers, and knew nothing of their origin. They were taller and darker than the Men of Bree and were believed to have strange powers of sight and hearing, and to understand the languages of beasts and birds.”

The Dunedain, unbeknownst to the inhabitants of the Shire and of Bree, patrol and protect these lands and the folk that inhabit them. Their mission is, by necessity, a secret one, with no glory or renown to be earned in its execution. Aragorn acknowledges this, not without a tinge of bitterness:

“‘Strider’ I am to one fat man who lives within a day's march of foes that would freeze his heart, or lay his little town to ruin, if he were not guarded ceaselessly. Yet we would not have it otherwise. If simple folk are free from care and fear, simple they will be, and we must be secret to keep them so.”

This resonates with the quote often attributed to George Orwell: “People sleep peaceably in their beds at night only because rough men stand ready to do violence on their behalf.”

Far to the south in the borderlands of Gondor the Rangers of Ithilien acted as an elite border patrol, interdicting infiltrating orc bands and forces of Haradrim en route to Mordor.

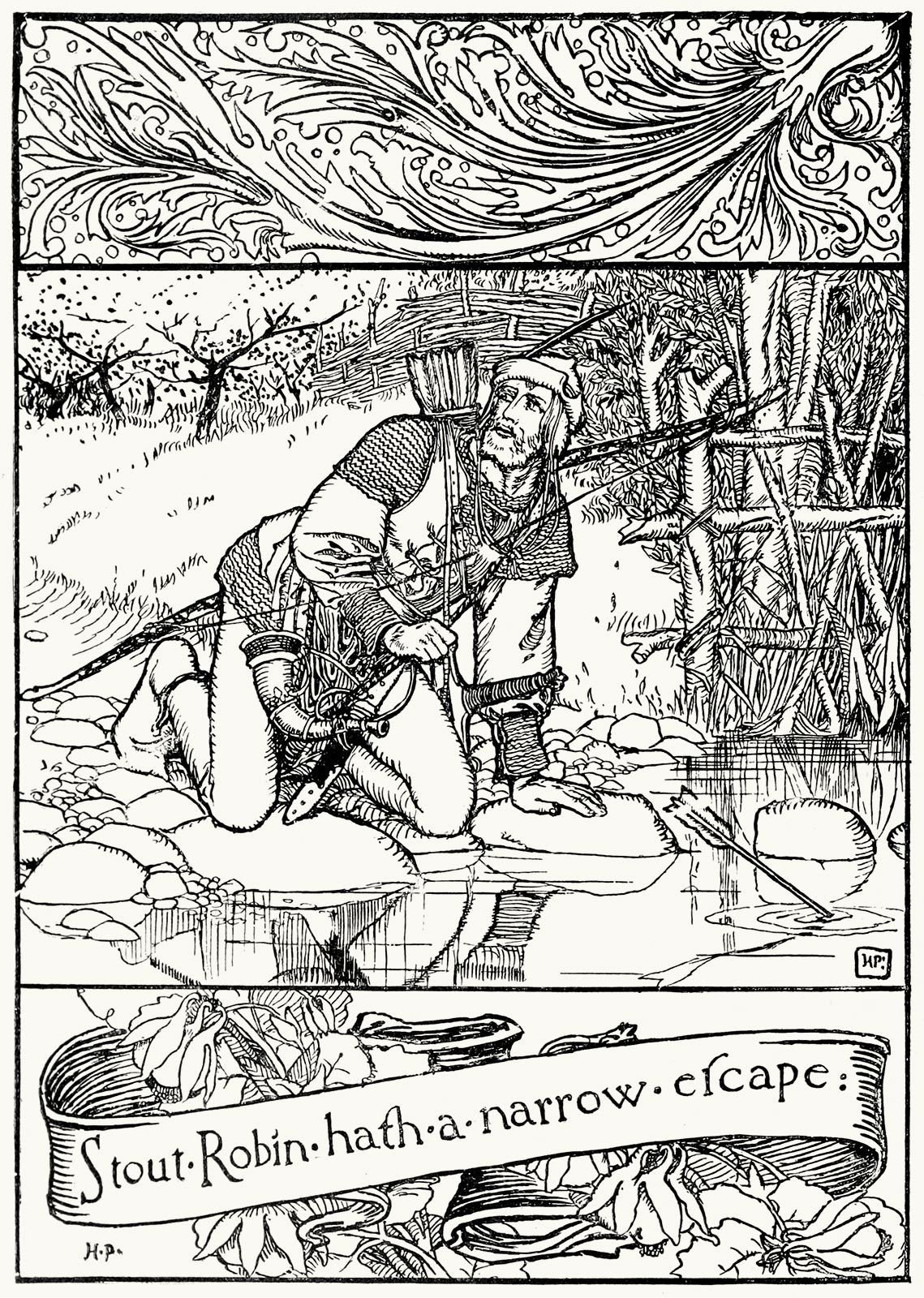

Tolkien’s depiction of the Ranger derives mostly from the English tradition — think of the Knight’s yeoman in the Canterbury Tales. Robin Hood — who, despite his outlaw status, might be thought of as a Saxon Ranger protecting the small folk from predatory Normans — may also have been an influence. Certainly the classic Howard Pyle and N.C. Wyeth illustrations of Robin Hood have influenced our vision of the medieval Ranger archetype.

We know that Tolkien had at least some exposure to American frontier tales that may well have helped shape his Rangers. Recalling the reading of his youth, Tolkien said that Treasure Island left him “cool.” He wrote:

“Red Indians were better: there were bows and arrows (I had and have a wholly unsatisfied desire to shoot well with a bow), and strange languages, and glimpses of an archaic mode of life, and, above all, forests in such stories.”

We don’t know just what he read, though he reportedly studied Longfellow’s “Song of Hiawatha” in college. It’s a safe bet that he knew Cooper’s Leatherstocking Tales, and Tom Shippey sees echoes of Cooper in the Fellowship of the Ring’s journey by boat down the River Anduin.

The archetype Tolkien formed out of his influences set the image of what the Ranger of fantasy looks like and does.

Another great creator of fantasy archetypes cleaved to a distinctively American model of the Ranger. Robert E. Howard tapped into his growing passion for the frontier history of Texas, mashed it up with place names and imagery adopted and adapted from the French & Indian War and Revolutionary War-era woodland frontiers of New York, and created a frontier society on the edge of Hyborian Age civilization, between Thunder River and the Black River that marked the border of the Pictish Wilderness.

“They were of a new breed growing up in the world on the raw edge of the frontier — men whom grim necessity had taught woodcraft. Aquilonians of the western provinces to a man, they had many points in common. They dressed alike — in buckskin boots, leathern breeks and deerskin shirts, with broad girdles that held axes and short swords; and they were all gaunt and scarred and hard-eyed; sinewy and taciturn.”

Such a man was Gault Hagar’s son, who featured in the unfinished “Wolves Beyond the Border,” part of a late-Conan spate of frontier tales that Howard produced, including “The Black Stranger,” and “Beyond the Black River,” widely regarded as among the very best of Howard’s work.

Conan himself is of a different class of Ranger — a natural-born elite among elites. This is immediately apparent to the Tauranian forester Balthus when Conan steps out of the brush in the Pictish Wilderness at the beginning of “Beyond the Black River.”

“… a tall figure stepped leisurely into the trail. The traveller stared in surprize. The stranger was clad like himself in regard to boots and breeks, though the latter were of silk instead of leather. But he wore a sleeveless hauberk of dark mesh-mail in place of a tunic, and a helmet perched on his black mane. That helmet held the other’s gaze; it was without a crest, but adorned by short bull’s horns. No civilized hand ever forged that head-piece. Nor was the face below it that of a civilized man: dark, scarred, with smoldering blue eyes, it was a face as untamed as the primordial forest which formed its background. The man held a broadsword in his right hand, and the edge was smeared with crimson.”

Conan’s woodcraft is of the highest order — good enough for him to stalk and kill a Pictish warrior in his own territory. That skill level traditionally distinguishes the elite from the garrison soldier. As Conan tells Balthus:

“I’m no soldier. I draw the pay and rations of an officer of the line, but I do my work in the woods. Valannus knows I’m of more use ranging along the river than cooped up in the fort.”

Conan is a mercenary, a barbarian in the pay of a civilized nation, stalking other barbarians with whom his people have a feud that, as he puts it “is older than the world.” This puts the Cimmerian squarely in a frontier tradition. Crow and Pawnee scouts served the U.S. Army for pay — and to carry on an old blood feud with the Lakota. Tonkawa scouts rode with Rip Ford’s Texas Rangers to get payback against their old enemy, the Comanche. The Army employed Apache scouts to run down other, militant Apaches in the 1870s and ’80s. Howard knew all of this.

The main action of Beyond the Black River is precipitated by Valannus assigning Conan a classic Ranger task — a capture-or-kill mission on a high-value target:

“Conan, Zogar Sag must die, if we are to hold Conajohara. You have penetrated the unknown deeper than any other man in the fort; you know where Gwawela stands, and something of the forest trails across the river. Will you take a band of men tonight and endeavor to kill or capture him? Oh, I know it's mad. There isn't more than one chance in a thousand that any of you will come back alive. But if we don't get him, it's death for us all. You can take as many men as you wish.”

“A dozen men are better for a job like that than a regiment," answered Conan. “Five hundred men couldn't fight their way to Gwawela and back, but a dozen might slip in and out again. Let me pick my men. I don't want any soldiers.”

Such a mission would have been familiar to Rogers Rangers, a force raised in the 1750s to counter the capabilities of the French and Indian masters of la petite guerre. It aligns even more closely with the bloody work of the Revolutionary War contingent known as Brady’s Rangers, who operated out of western Pennsylvania beyond the Ohio River in the territory of the Shawnee, Delaware and Mingo, rescuing captives, gathering intel, and engaging enemy forces.

Captain Samuel Brady may well have been the most skilled, and most effective of the Rangers of the American frontier. Ace frontier historian Ted Franklin Belue cites a contemporary description of Brady that lines up perfectly with many of Howard’s dark Celtic heroes, particularly one notably “pantherish” Cimmerian:

Except, maybe, for Sam Brady’s rack of shoulders, piercing blue eyes, and black, shoulder-length hair, little distinguished him from other woods-runners. In habits and mannerisms, in quirks and traits he resembled them. He stood about six feet, his hard body of bare subsistence never topping 170 pounds. Sam’s lithe frame and quick, easy step put one in mind of a cat tensing before its prey, gathering itself on its paws in readiness to pounce. As I write in ‘The Hunters of Kentucky,’ John Cuppy, the last Brady scout to die (at 100 years, 3 months, and 17 days), framed his Captain in terms akin to a Hollywood matinee idol:

“Brady was . . . tall, large—with muscles of steel, when he ran he appeared to fly over obstacles, and never appeared fatigued. He could throw a tomahawk straighter and further than anyone I knew.”

Operating out of Pittsburgh from the late 1770s during the darkest years of the American Revolution, Brady led a contingent of hand-picked rangers on deep-penetration patrols into Indian-held territory between Fort Pitt and the Sandusky towns, headquarters of the British-aligned militant warriors of the Shawnee, Delaware, Mingo and Wyandot nations. Think Vietnam War LRP/LRRP (long-range patrols/long range reconnaissance patrols) or maybe Selous Scouts in the Rhodesian Bush War. These men were operators of the first order.

He and his men rescued captives and stacked up a significant body count — sometimes in the most callous and brutal ways. It was a brutal time and place.

Sam Brady should be on some Mt. Rushmore of special operations forces, yet, despite his effectiveness, Brady is little known outside of the fraternity of frontier obsessives.

Of course Howard was deeply familiar with the most famous unit of Rangers in American history — the Texas Rangers. The paramilitary force was raised to protect young Texas settlements from incursions by Mexicans who continued to consider the borderlands their own, even after the 1836 war of independence, and from Comanche raiders who came out of the wilderness bringing terror and destruction. If ever there was a foe that could freeze a heart and lay a little town (or a homestead) to ruin, it was the Comanche.

Howard was greatly enamored of one Ranger in particular — William A. “Bigfoot” Wallace.

I am convinced that Wallace was on hand when Conan famously strode out of the shadows of legend, fully-formed, into the consciousness of Robert E. Howard. In his correspondence with H. P. Lovecraft, Howard wrote:

“Have you heard of Bigfoot Wallace? When you come to the Southwest you will hear much of him, and I’ll show you his picture, painted full length, hanging on the south wall of the Alamo — a tall, rangy man in buckskins, with rifle and bowie, and with the features of an early American statesman or general. Direct descendant of William Wallace of Scotland, he was Virginia-born and came to Texas in 1836 to avenge his cousin and his brother, who fell at La Bahia with Fannin. He was at the Salado, he marched on the Mier Expedition and drew a white bean; he was at Monterrey. He is perhaps the greatest figure in Southwestern legendry. Hundreds of tales — a regular myth-cycle — have grown up around him. But his life needs no myths to ring with breath-taking adventure and heroism.”

The qualities and capabilities of the Ranger are consistent, whether we are talking about a mythic archetype, a historical figure, or contemporary light infantry soldiers. The Ranger is exceptionally physically fit and capable, just in the manner Ranger Cuppy described his Great Captain. He is skilled in navigating in strange wilderness terrain — remember: Not all those who wander are lost. He is skilled at arms, with a ranged weapon, be it bow or long rifle, and with melee weapons, be they sword, or long knife or belt ax (tomahawk). The Ranger must be committed to the defense and protection of small folk who may not even be aware of the work they do.

The Ranger is a noble, if hard-bitten archetype. It seems that no matter what cultural storms and cataclysms may buffet him, he will endure, for, as Bilbo Baggins wrote of his friend Strider: “The old that is strong does not wither; deep roots are not reached by the frost.”