Interpretation of the Romantic-Decadent Medusa-Harlot

Possible spoilers ahead for Robert E. Howard’s "A Witch Shall Be Born," The Happy Prince (2018), Salomé (2013), Conan the Barbarian (1982), the works of Clark Ashton Smith, Wilde’s Salome, and more.

“The very objects which should induce a shudder—the livid face of the severed head, the squirming mass of vipers, the rigidity of death, the sinister light, the repulsive animals, the lizard, the bat—all these give rise to a new sense of beauty, a beauty imperilled and contaminated, a new thrill” (Praz 26).

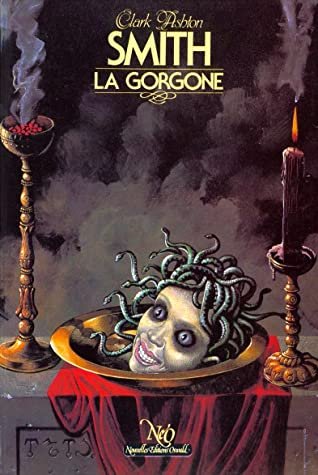

Clark Ashton Smith, who wrote some stories in the sword-and-sorcery genre, also wrote other types of powerful pieces, those which are not sword and sorcery but are instead Romantic and aesthetic and, sometimes, Decadent; those aesthetic writings are the ones I love, and I love them as much as I love his most macabre works.

There is a certain Romantic element which I greatly adore, one that can be seen in Smith’s piece of poetry “The Harlot of the World,” and it is this glyph that really connects this poem to the tree of Romanticism, the glyph that speaks of harlotry, the femme fatale, the cruel feminine, the Medusa, evil beauty.

“This glassy-eyed, severed female head, this horrible, fascinating Medusa, was to be the object of the dark loves of the Romantics and the Decadents throughout the whole of the century” (Praz 26–27).

The Romantic-Decadent harlot takes many diverse forms, incarnations, and appearances, even in some tales that are within the genre of sword and sorcery. What can we learn from her? Learning more about such matters can help readers understand the ways Romanticism connects with the work of Clark Ashton Smith. I think one of Smith’s most Romantic pieces is his “The Harlot of the World,” which brings to life a harlot character, a destroyer, a metaphor for perverse forces of life and death. This poem uses one of the most powerful features of Romantic literature: an eidolon of deathly, debased female essence, as destructive and captivating as a Gorgon.

Princess Salomé is a great example of such a beast that should not be gazed upon. Around her, sight is related with danger and wanton. Looking at her is peril. She is regal and prostitute. Attraction and danger. Take a look at these three pieces from Wilde’s Salome:

THE YOUNG SYRIAN—How beautiful is the Princess Salomé to-night!

THE PAGE OF HERODIAS—You are always looking at her. You look at her too much. It is dangerous to look at people in such fashion. Something terrible may happen. (Wilde, 1927, 1930, page 4)THE PAGE OF HERODIAS—What is that to you? Why do you look at her? You must not look at her. . . . Something terrible may happen. (Wilde, 1927, 1930, page 8)

“Thou wouldst have none of me, Jokanaan. Thou rejectedst me. Thou didst speak evil words against me. Thou didst bear thyself toward me as to a harlot, as to a woman that is a wanton, to me, Salomé, daughter of Herodias, Princess of Judæa!” (Wilde, 1927, 1930, pages 54–55)

The Medusa-harlot, a Romantic symbol, is potent and hypnotizing; a wanton such as she is a very important device in the languages of Romanticism, dark Romanticism, and Decadence. The Romantic harlot can be whore or virgin; what is necessary is that she be debased and symbolic of an aesthetic or spiritual kind of prostitution, of vice, defilement.

“Nevertheless a line of tradition may be traced through the characters of these Fatal Women, right from the beginning of Romanticism. In this pedigree one may say that Lewis’s Matilda is at the head of the line: she develops, on one side, into Velléda (Chateaubriand) and Salammbô (Flaubert), and, on the other, into Carmen (Mérimée), Cécily (Sue), and Conchita (Pierre Louys). . . .” (Praz 201).

Can that tradition include Lady Macbeth? Gertrude of Hamlet? Salomé of Oscar Wilde’s Romantic tragedy Salome?

Now let us here look at a passage from Clark Ashton Smith’s poem “The Harlot of the World.”

“O Life, thou harlot who beguilest all! / Beautiful in thy house, the golden world” (Smith, page 299).

And we should also consider this other fragment from that same poem:

“Innumerous like the stars or like the dust, / Nations and monarchs were thy thralls of yore: / Unto the grave’s old womb forevermore / Hast thou betrayed the passion and the lust.” (Smith, page 300).

Let us compare those with a piece from Oscar Wilde’s Decadent poem “The Harlot's House.”

“Then turning to my love I said, / ‘The dead are dancing with the dead, / The dust is whirling with the dust.’ / But she, she heard the violin, / And left my side and entered in: / Love passed into the House of Lust” (Wilde, 2013).

Dust. Lust. Love. Death. Houses of harlotry.

With such romantic, decadent symbols, there is invoked a kind of oblivion, a kind of petrification. Ashes, sand, earth, dust, and stone. Paralyzed. These poems evoke a sensation of freezing fear, freezing helplessness, directed towards and attached to an ideal of femmes fatales. But there is also something hot about it. Like Hell. Ice and fire.

And let us also take a glance at a part from Robert E. Howard’s sword-and-sorcery novella "A Witch Shall Be Born."

“The beautiful face in the disk was convulsed with the aspect of a fury; so hellish became its expression that Taramis, cowering back, half expected to see snaky locks writhe hissing about the ivory brow” (Howard, chapter 1).

Howard’s "A Witch Shall Be Born" gives us a character named Salome who is surrounded with symbols and characteristics and imagery of light, venom, snakes, fury, hideousness, beauty, lust, mystery, the moon, seduction, cruelty, vulgarity, harlotry, and the power to command and manipulate.

“Some were slain at birth, as they sought to slay me. Some walked the earth as witches, proud daughters of Khauran, with the moon of hell burning upon their ivory bosoms. Each was named Salome. I too am Salome. It was always Salome, the witch.” (Howard, chapter 1).

But let us look at another relevant, interesting piece from “A Witch Shall Be Born”:

“He would have made me queen of the world and ruled the nations through me, he said, but I was only a harlot of darkness.” (Howard, chapter 1).

Like Wilde’s and Smith’s poems, Howard’s novella has also been touched by a similar design of Romanticism. These works remind of the dark beauty, death, love, attraction, and destruction that in art surrounds harlots, malevolent witches, and defiled females. As symbols, these kinds of transgressive elements partly signify the fatal edge of human existence, the duality, the chaos, the abyss; they are different kinds of deathly desires; they are the irresistible corruptions in life and in exquisiteness; they are also illustrations of the pull toward evil essences, which form even the purest things. Most of Howard’s writings appear, in my opinion, to hold an attitude which is hotly opposed to the decadence such symbols represent; many of Clark Ashton Smith’s writings appear, on the other hand, to show more of a despair and yet an affinity for these symbols, these vampiric flowers.

This subject reminds me of Rupert Everett’s marvelous, lush film The Happy Prince (2018): a romantic and profound film proffering audiences scintillating gems such as a glimpse of the Gothic, fleeting kisses from the macabre, and a quick bite of brawling even; moreover, and to cast light on the item ad rem, it would be apt for me to mention that one of the film’s most clever scenes, though a short moment, alludes to Salomé, in which certain actions and symbols conjoin her character beside allure, vice, and perversion.

I must also mention Salomé (2013), directed by Al Pacino. Interestingly, it exhibits a character wielding an exotic sword redolent of something with which Robert E. Howard’s Conan might fight (see especially: John Milius’ film Conan the Barbarian). The costumes in Al Pacino’s Salomé were ridiculously and woefully inappropriate, as they were contemporaneous with today’s manner of corporate formalwear. Obviously, it isn’t a movie that should be expected to have any substantial fighting or ruthless carnage; although, it does hold a hint of the ghoulish. Its dance scene and the high performances throughout the film are delicious. Its Salomé character is enraged, severe, even arch at times, but more often like a scourge or a Harpy, or a Gorgon, than a woman. Even in this film, Salomé is connected with the harlot, the moon, and the suffering of rulers.

If one looks carefully, one can find traces of Romanticism in some the best writings of Clark Ashton Smith and Robert E. Howard. What’s more, one can find a hint of Romanticism in many sword-and-sorcery stories. Romanticism has always had a strong influence on the sword-and-sorcery genre.

One of my favorite Romantic figures is the Medusa, the femme fatale, the symbol of macabre beauty. I like when I see it in sword-and-sorcery pieces. In my mind, I see the Medusa in the harlot, and vice versa, for they are both venomous and seductive in their horror and charm.

Smith used the harlot-element well in his “The Harlot of the World,” and I believe the result inadvertently demonstrations an attraction to and a fear of the grotesque.

The Decadents, like Baudelaire, used it in ways that can symbolize a lust for transgression.

“The final metamorphosis both of the Fatal Man and of the Fatal Woman can be seen in Baudelaire’s Métamorphoses du vampire.” (Praz 281).

Let us take a look at Baudelaire’s poem “The Metamorphoses of the Vampire.” In it, we are given sex and snake symbols: “Twisting and writhing like a snake on fiery sands, / Kneading her breast against her corset’s metal bands,” (Baudelaire, page 253). Furthermore, the irresistible temptation and revolution of damnation comes alive—“On all those mattresses that swoon in ecstasy / Even helpless angels damn themselves for me!’ (Baudelaire, page 255). The pure and the impure are joined as one. Baudelaire in this poem displays a portrayal of female vampirism, a she-parasite of corruption and orgasm, as is especially evident through this: “When she had drained the marrow out of all my bones, / When I turned listlessly amid my languid moans,” (Baudelaire, page 255). The harlot, a submissive and dominant icon, is in full power in this poem—“I am, my dear savant, so studied in my charms / That when I stifle men within my ardent arms / Or when I give my breast to their excited bites,” (Baudelaire, page 255). She has a connection with the cosmos and with the moon: “I take the place for those who see my naked arts / Of moon and of the sun and all the other stars” (Baudelaire, page 253).

Wherever she appears—in poetry, in sword-and-sorcery stories, in film, on the stage, in literature—the Romantic-Decadent harlot is often a vampire and a Gorgon. She is a symbol of that cosmic force which is coupled with and yet outside of nature, connected with and yet beyond lust. She is a paralyzing, suffocating, hypnotic force of dread and seduction. She is a reminder of our mortal duality, our dance with decay; or, she is an erotic memento mori signifying both a spiritual petrification and a change, an upheaval. A revolutionary force of a type of vanity which brings infernal transformation. Metamorphosis and petrification combined. An evil leading the way to that rarest of beauty which mysteriously summons the sublime.

Matthew Pungitore’s short story “Wychyrst Tower” appeared in Cirsova Magazine (Winter 2021).

He has written various articles for the DMR Books blog. In the past, he has done volunteer work for the Hingham Historical Society. Matthew is the author of The Report of Mr. Charles Aalmers and other stories, Fiendilkfjeld Castle, and Midnight's Eternal Prisoner: Waiting For The Summer. Matthew graduated with a Bachelor of Science in English from Fitchburg State University.

If you’re curious, visit his BookBaby author-page.

Contact him at: matthewpungitore_writer@outlook.com

WORKS CITED

Baudelaire, Charles. “The Metamorphoses of the Vampire.” The Flowers of Evil. By Charles Baudelaire. Ed. James McGowan. Trans. James McGowan. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2008. Print.

Howard, Robert E. “A Witch Shall Be Born.” Delphi Collected Works of Robert E. Howard (Illustrated) (Series Four Book 21). Robert E. Howard. 1st ed. Delphi Classics, 2014. Kindle.

Praz, Mario. The Romantic Agony. Translated by Angus Davidson. Foreword by Frank Kermode. 2nd ed. London: Oxford University Press, 1970. Print.

Smith, Clark Ashton. "The Harlot of the World." The Dark Eidolon and Other Fantasies. By Clark Ashton Smith. Ed. S. T. Joshi. New York, NY: Penguin Classics, 2014. Print.

Wilde, Oscar. “The Harlot’s House.” The Complete Poetry. Oscar Wilde. e-artnow, 2013. Kindle.

Wilde, Oscar. Salome. E. P. Dutton & CO., INC. 1927, 1930. Inventions by John Vassos. Print.