Poul Anderson: Going For Infinity (2002)

Poul Anderson strode up the Bifrost Bridge to Valhalla twenty years ago today. That passing didn't receive the ballyhoo that Asimov's demise garnered a decade earlier or that Arthur C. Clarke's extinction got a decade later. It should have, but it didn't. That is the subject of a future post.

No, today we're here to celebrate the career of one of the greatest writers to ever grace the SFF genres with his blazing talent and amazing intellect. Specifically, the capstone of his career and love-letter to his fans: Going For Infinity.

That career-retrospective of Anderson's work was published almost exactly nineteen years ago in June of 2002. Despite it debuting almost a year after his passing, GFI was a project that had the whole-hearted participation of Poul. He provides a lengthy 'Introduction' and short intros for every story in the collection. In many ways, this was his last will and testament regarding his career in SFF. I'll let Poul speak for himself with several quotes from his 'Introduction'.

'You hold this book thanks largely to Robert Gleason [at Tor Books]. Having been my editor for a long time, he felt that there ought to be something covering a still longer span, my writing through the half century since it first appeared. What he had in mind was not simply another collection, but a retrospective—besides stories, something about their origins, backgrounds, contexts, a historical overview of the science fiction and fantasy field throughout those decades.'

'Let me just say that good science fiction and fantasy are entertaining. They engage our attention in ways agreeable and often challenging. Good art of every kind does, of course, including the most solemn or tragic. In that sense, Mozart’s Requiem and Shakespeare’s Hamlet are entertaining...'

Mr. Anderson isn't apologising for the genres he'd chosen to write in. Poul was always a stalwart defender of Speculative Fiction. He gives props to Shakespeare, which most of the Forefathers of Sword and Sorcery and nearly all of the First Dynasty of Sword and Sorcery also did.

Poul Anderson circa 1960.

Poul goes on to describe his ancestry and childhood:

'My ancestors were mostly Danish, with a few dashes of other nationalities... (...) As small boys, my brother [John] and I were excited on getting the impression that one of our forebears had been a pirate, then disappointed to learn that he was actually a perfectly legitimate privateer in the Napoleonic Wars,who afterward settled down as a merchant in Copenhagen.'

'[My mother, Astrid] and my father had been schoolmates for a while in Denmark, but lost touch with one another. By sheer chance, they met again. Soon they were dating, and in January 1926 they were married. I joined them on 25 November of the same year. My mother named me after her own father, Poul... (...) This was in Bristol, Pennsylvania. I have no memory of that town, because I was an infant when my father got a new job and we moved to Port Arthur, Texas.

He did well in those Depression years, becoming chief estimator at the Texaco offices. My brother John, born in 1930, and I enjoyed a happy boyhood—except for school—in a pleasant suburb that still had plenty of vacant lots for kids to play in. (...) I hope all this detail hasn’t been too boring. The aim has simply been to look at some important influences on me as a writer. You can see where certain recurring themes in my stories come from—the sea, Scandinavian history and culture, a solid and loving home life.'

Anderson's home life was up-ended when his father died in a car accident in late 1937--Poul was eleven years old. His mother took him and John to Denmark. War-clouds gathered and she soon brought her sons back to the States, with the three eventually ending up in Minnesota. Poul spent his teenage years working hard on the farm his mother had bought. Then...

'Rejected for military service because of my scarred eardrums [due to a childhood ailment], I entered the University of Minnesota in 1944, with a major in physics, minors in mathematics and chemistry. Though I did not become a scientist, this training has clearly been basic to much of what I do and how I go about it.

In those years I finally got up the courage to submit my stories, and sold two or three while still an undergraduate. I did not go on to graduate studies; the money was exhausted. Instead, I supported myself precariously by writing while I searched for a job. The search grew more and more half-hearted, until presently I realized that a writer was what nature had cut me out for. When I discovered and joined the Minneapolis Fantasy Society, it led to enduring friendships, some love affairs, and a network of fellow enthusiasts around the world. That’s where this book [Going For Infinity] properly begins.'

That's the end of the introduction, which brings us to the actual stories. These tales are not presented in chronological order. Since a chronological order appears to have been Gleason's initial idea, the fact that the stories are not presented in such a fashion would indicate that the order of the stories was Poul's personal choice. I won't attempt to read the tea leaves concerning what Mr. Anderson's sequencing means, but he seems to have wanted to communicate/illustrate something in that regard.

The first story is 'The Saturn Game' (1980), which narrates a voyage to--and arrival at--Saturn and its moons. Here is Poul's excerpted intro:

'There are times when somehow the spirit opens up to the awe and mystery of the universe. Afterward, dailiness returns; but those minutes or hours live on, not only as memories. They become a part of life itself, giving it much of its meaning and even its direction.They have come to me when I have been camped out under skies wholly clear and dark, more full of stars than of night. (...)

My earliest that I recall goes back to childhood, age six or seven or thereabouts. We lived in a new suburb, with plenty of vacant lots for boys to romp in and no street lights. Nor did anybody anywhere have air conditioning. One evening after a hot summer day we went outside to enjoy the cool. Twilight gathered, purple and quiet. Stars began to blink forth.

“That red one,” said my mother. “Is that Mars?”

“I believe so,” answered my father. He had made a few voyages with his own father, a sea captain, when navigation was mainly celestial.

“Do you think there’s life on it?”

“Who knows?”

Wonder struck through me like lightning. I’d learned a little about the planets, of course. Now suddenly it came fully home to me, that I was looking at a whole other world, as real as the ground beneath my feet but millions of miles remote and altogether strange.'

Poul never considered himself much of a poet, but that is some fine poetic prose right there.

The next tale is 'Gypsy' from 1950. This is part of Anderson's intro for it:

' “Gypsy” is the earliest [story of mine] that seems worth including here. I could do it better nowadays. Perhaps I wouldn’t do it at all, because the “science” in it is mostly what engineers and my son-in-law Greg Bear call arm waving. Still, probably more [SF] stories than not require such postulates.'

Anderson was honest enough to admit the 'mulligan' that so many 'Hard SF' authors and fans give themselves: Faster Than Light Travel. FTL is literally less likely than almost anything ERB put into A Princess of Mars, yet Starman Jones is still considered 'SF' and APoM is not.

The third story in Going For Infinity is 'Sam Hall', a much-anthologized tale that--unlike some 'classics' from the 'Golden Age of SF'--richly deserves it. It's not about adventures in a far-flung galaxy. Instead, it tells the story of a lone man fighting against a computerized, totalitarian state in the near future. Here's Poul:

'By 1950 I was no longer living hand to mouth but had enough reserves for travel. That year a friend and I took a cross-country drive to a conference in New York. Along the way we visited MIT to see the Bush differential analyzer, the world’s most powerful computer. It was an awesome sight, tall stacks of blinking vacuum tubes reaching back through a cavernous chamber...

In 1951 I spent several months bicycling and youth hosteling abroad. Those were magnificent months, but unavoidably had their few small annoyances. One was the requirement to fill out a silly little form everywhere I stayed, with such information as my passport number, where I had last stopped, andwhere I was going next—a form that would only molder in local police archives. No one ever actually looked at the passport. We’ve since been afflicted with similar things over here, but America was more innocent then. Occasionally, somewhat childishly, I let off steam by registering as Sam Hall, the subject of a rowdy old ballad we often sang in the MFS [Minneapolis Fantasy Society]. (...)

Many things in ['Sam Hall'] are now long since obsolete, most conspicuously the computer system itself, but there seems to be scant point in revision. I think it still has something important to say. At the very least, it forecast computer crime!'

The next tale is 'Death and the Knight'. This was Poul's last story in his beloved 'Time Patrol' series.

An excerpt from his intro:

'Just a few years ago, Katherine Kurtz invited me to contribute to a book she was getting together, Tales of the Knights Templar [1995], and it seemed a good place for another. Since that paperback is probably less readily available by now, I’m letting this item represent the series...'

The next up is 'Journeys End' from 1957...

'Tony [Anthony Boucher] accepted and published the following little piece. This was rather early on and I could do it better today, but will let it stand as an example of the diversity in his magazine. He told me what a struggle he had with copy editors and proofs to keep an apostrophe out of the title, which goes to show what kind of line editor he was.'

Anderson's tale is one of two lonely telepaths finding each other. It demonstrates more acuity in regard to the human condition than can be found in most of Heinlein, Asimov and Clarke’s works. I’ll leave it at that.

The sixth story is 'The Horn of Time the Hunter'.

'My thought was that if this kind of traffic [traveling near the absolute limit of the speed of light] became common, the traffickers would grow ever more isolated culturally from dwellers on planets. They’d evolve their own society, whose members seldom married outside it; and there could be periods of history in which they were the objects of cruel discrimination or even persecution. (...) Here it is, then, a far-future incident, perhaps important only to the people involved, but to them overwhelming. History knows of many such.'

Next is 'The Master Key', one of Anderson's many tales of Nicholas van Rijn, free trader of the starways.

'Elsewhere I have written at some length about [John W. Campbell]—the tribute is in All One Universe —and shan’t repeat much here. Geography prevented my becoming as close to him as to Tony [Boucher], but I was among those privileged to have a fireworks correspondence with him, and when we met in person it was always more than cordially. Our long hammer-and-tongs arguments about countless different things only added savor. From father figure he evolved to dear friend.

It was with him that Nicholas van Rijn exploded forth. While some readers couldn’t stand this burly, beery, uninhibited merchant prince, on the whole he was probably the most popular character I ever hit upon, and the stories about him enjoyed a long and lusty run.'

The eighth story in Going For Infinity is 'The Problem of Pain'. Taking place within Anderson's 'Technic History' setting made famous by the Dominic Flandry tales, it is set on one of the colonized human planets:

'I’d been spinning yarns about Dominic Flandry, intelligence agent for a decadent Terran Empire. It had occurred to me that van Rijn could well have lived centuries earlier and now be remembered in folklore. How the exuberant libertarianism of the early interstellar period devolved through the Hansa-like Polesotechnic League and its collapse to the Empire, and what came after, gave rise to a number of stories, each self-explanatory but all parts of a “future history.”

In it, humans and Ythrians jointly colonize a world and gradually develop a hybrid society like none ever seen before. The details are in a novel, The People of the Wind, but several briefer tales take place here at various stages of the development. This one harks back to the period of exploration before settlement, when the name Avalon had not yet been bestowed.'

The next story is a short sequel to Poul's classic novel, The High Crusade:

'Again we jump back through time, now to 1960. That was the year when Astounding serialized The High Crusade. This romp remains one of the most popular things I’ve ever done, going through many book editions in several languages. George Pal had thoughts of filming it, but then he died. Eventually a German studio did. I’ve avoided seeing the result after being told on good authority that it’s a piece of botchwork, and suggest that you might enjoy the novel more.

Briefly put, in the story the evil Wersgor empire has been expanding through space in leapfrog fashion, as its scouts find those widely scattered planets that are suitable for colonization—which happens to mean similar to ours. One lands on Earth. The site is an English village, the year is 1345, and the local baron, Sir Roger de Tourneville, is making ready to depart with the troop of free companions he has been gathering to join King Edward III in France.

As usual when they come upon intelligent natives, the Wersgorix immediately set about terrorizing them, dropping a gangway to the ground, stepping forth, and opening fire with their energy handguns. It is a rude shock to them that the air is suddenly full of crossbow bolts and clothyard arrows, whereafter cavalrymen gallop up the gangway, followed by foot soldiers, into the ship. Only one Wersgor survives. [Spoilers follow].

Maybe this is an unnecessarily long synopsis. It’s meant to give the background for a short story I wrote years afterward [published in 1983 in Ares Magazine] and reprint here as a representative of the novel.'

The tenth tale is 'Windmill, part of Anderson's 'Maurai' series.

'The Maurai chronicles began with a novelette, “The Sky People,” and ended with a novel, Orion Shall Rise. The basic premise came from a book by Harrison Brown, The Challenge of Man’s Future, published long ago but still well worth reading, very pertinent to the world around us today. (As said earlier, I steal only from the best sources).

The author pointed out that our civilization got started by exploiting a treasury of ores, coal, petroleum, timber, fertile soil, and everything else. As these have grown scarcer and more expensive, we have so far found substitutes, ways to economize and recycle, and generally keep going. Indeed, on the whole, our high-tech societies grow ever richer, and could do better yet were it not for their wars, ideologies, and other tragic, all too human foolishnesses.'

The next tale is an excerpt from Poul's classic heroic fantasy novel, Three Hearts and Three Lions. Here's what he had to say:

'So far I’ve been recalling a career in science fiction. I’ve also written fantasy. The distinction between the two genres is as tenuous as the science in the first-named often becomes. Tony Boucher once told me that, judging by the mail he got, most of his readers actually preferred fantasy to science fiction but didn’t know it.

After all, as I’ve remarked elsewhere, the evidence for, say, life after death and at least one God is, at the present state of our knowledge, probably better than the evidence for psionic powers, time travel, or travel faster than light. Which themes belong in which category seems pretty arbitrary. At most, one can argue that the underlying premise of science fiction is the scientific premise itself, that the universe makes sense and no matter what surprises we come upon, they’ll fit in with what we already know. Fantasy is under no such obligation.

But we don’t absolutely know that the scientific premise is true. We simply have to make it, or else give up trying to learn more with any reasonable degree of certainty. And it has in fact served us well. To me, whether a story should be hard or soft science fiction depends merely on what the storyline wants, and as for fantasy, let ’er rip!

When Tony bought a short version of Three Hearts and Three Lions way back in 1953, he asked me to throw in some stuff about parallel universes or whatever, to satisfy the demand for “scientific explanation.” I was quite willing. (...)

The following incident occupies two chapters I added to the full-length version. Among other things, it’s a mystery story, with clues to the solution of the puzzle. I wrote it that way in Tony’s honor.'

Anderson’s short intro had this to say about 1962's 'Epilogue':

'Almost forty years have passed since then [1962], and my text shows its age in several ways. However, the concept still seems fresh, and I’ve let most of the “anachronisms” stand, such as the use of English rather than metric units. Feminists who object to the heroine being referred to as a “girl” are reminded that back then the word was a perfectly polite synonym for “young woman,” and invited to consider the role she plays.

After John Campbell bought the novelette he sent me one of his typically long, disputatious letters, maintaining that things couldn’t work out that way. Nevertheless he ran the story exactly as written.'

'Dead Phone' was one of Anderson's non-SFF mystery stories he wrote back in the '60s.

'The hero of most [of my mystery stories] was Trygve Yamamura, Hawaiian-born to a Japanese-American father and a Norwegian mother, eventually a private detective in Berkeley, California. Skilled in martial arts, he never used violence except when there was absolutely no choice, and then only when he absolutely must, being a gentle soul as well as an incisive thinker. I would have liked to continue with him, but was earning so much more by science fiction that it became impractical.'

'Goat Song'--a literal translation of 'tragedy' from the Greek--won both the Hugo and Nebula for 'Best Novelette' in 1973. When that meant something.

In 1966, Poul and his wife attended a small SF writers' conference in Pennsylvania. Here is his account of the genesis of 'Goat Song':

'On one of those evenings Harlan Ellison felt like doing a new story. He settled down with his typewriter in the otherwise empty dining room. From time to time he’d pop out into the smoky, boozy, noisy, cheery turmoil, shout a question at someone, get a reply, and pop back in. I remember he asked me about a point in Norse mythology and, caught off guard, I gave him a not-quite-correct answer; but no matter. Next day we all saw the story. It was “I Have No Mouth and I Must Scream”—a title which, by the way, came from a cartoon by fan artist, William Rotsler.

I think it was these associations as well as its power that made it haunt me. No doubt Cocteau’s film Orpheus had some influence too. Finally everything crystallized as “Goat Song.” About the only similarity between the two science fiction tales is the concept of human personalities preserved after death as data in a giant, probably quantum-mechanical computer system, for eventual resurrection either into virtual reality or as downloads into new bodies. Harlan didn’t have a patent on it, but it was pretty new at the time, and I thought it proper to request his okay, which he graciously gave. The story quickly sold to a well-paying magazine, but hadn’t been published when the magazine folded.

After it had languished for years, I got it back (my thanks to Barry Malzberg for advice about what to do) and placed it in Fantasy and Science Fiction. It was well-received, winning awards and being reprinted several times, though not recently. How I wish Tony [Boucher] could have seen it. But he had long since resigned his editorship, and died in 1968.'

Concerning his story 'Kyrie' (1968), Poul had this to say:

'Besides employing the physics as carefully as I was able to, I brought in some rather fantastical concepts, not only faster-than-light travel by way of hyperspatial jumps but a being that is mostly a plasma vortex and telepathy across cosmic distances. That’s what the story wanted. It’s generally best to go along.'

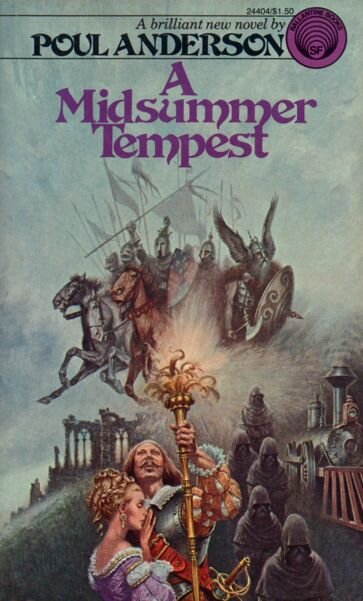

Next up is an excerpt from Anderson's novel, A Midsummer Tempest:

'The period in which this was written, the late ’60’s and early ’70’s, saw a renaissance of the whole [fantasy] field. It had lain long in the doldrums, most of what appeared being dull and derivative, supernovas like Fritz Leiber’s The Big Time doubly dazzling by comparison. Such an atmosphere deadens almost everybody. One doesn’t want to be a hack, one tries one’s damnedest for freshness, but without stimulation from others it’s bloody hard—as vicious a circle as ever there was. Now, almost overnight, came any number of new writers—original, vivid, explosive with new ideas and new ways of storytelling. They rekindled the fire in old-timers too. How these things happen is a mystery. I don’t think it’s merely a question of statistical fluctuations. But, anyway, they happen. I believe some of my own best work was done then, and like to believe that the standard has not fallen.

The evidence has become strong that our universe is flat, not closed as was commonly thought in those days. Finally, although "A Midsummer Tempest” proved to be caviar to the general, it’s a special favorite of mine, if only because it was sheer joy to write.

It’s my homage to Shakespeare—not that I can hold a candle to him, but here was a chance to drop all modern conventions and let the language roll whither and however it wanted to. The setting is a world in which his plays are not fiction but reports of historical fact. This means that Hamlet really lived, Bohemia did once have a seacoast, and on and on. In fact, since almost everybody in the chronicles spoke Elizabethan English, and purely English types such as Bottom were to be found in such places as ancient Greece, the Anglo-Israelite notion must be true. They have had a slight technological edge on us—consider, for example, the eyeglasses mentioned in King Lear or the cannon mentioned in King John—so it’s plausible that an Industrial Revolution would begin in the seventeenth century. Educated people commonly talk in blank verse, often ending in rhymed couplets, and sometimes members of the lower classes do, too. I’d played with the notion for years.

Then at last Karen [Anderson, my wife] suggested that the period be the English Civil War and the hero Prince Rupert of the Rhine. Suddenly everything crystallized for me, and I was off on my romp.'

Poul and Karen attended a CONTACT conference in 1999. 'The Shrine of Lost Children' was the result:

'A couple of Japanese guests [at the conference] were impressed enough to start their own organization. Karen and I were invited to its third meeting. In return, we were asked to provide a plausible world and dwellers at a real star within twenty light-years, so that radio communication wouldn’t be too slow. We put in quite a lot of time and effort, and I may yet get a novel out of it. In that case, I promised, there will be at least one important Japanese character! The event took place at a meeting center where everybody stayed in dormitory style—all by itself, a unique experience for us.

Afterward we traveled around for a while on our own. It’s an expensive country, but at our age this was an opportunity we couldn’t afford not to take advantage of. I’ve observed earlier how close-knit the heart of the science fiction world still is. You can meet somebody in person for the first time and instantly be good friends. We found it doubly true in Japan, where everybody was overwhelmingly kind and generous.

So, returning home, what else could I do but make my story a tribute to that beautiful land and her people?'

The final tale in Going For Infinity is 'The Queen of Air and Darkness' from 1971, which won the Hugo, Nebula and Locus for that year. A stone-cold Anderson classic.

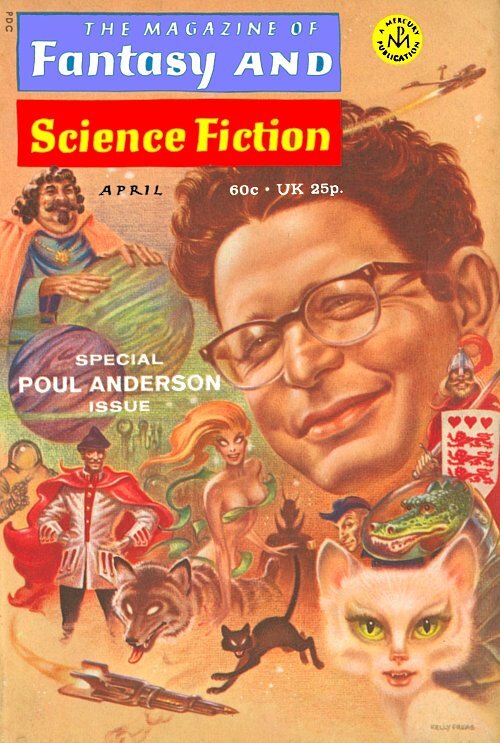

'I think it was under Edward Ferman that [The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction] started occasionally dedicating a particular issue to a particular writer, who contributed a feature story and was portrayed on the cover, while an appreciative essay or two by colleagues and a bibliography also appeared. Certainly it was Mr. Ferman who, in 1971, did this for me—a stunning honor, seeing that it had earlier come to Fritz Leiber and Theodore Sturgeon. The painting by Kelly Freas still hangs in my study, along with my investiture in the Baker Street Irregulars and several Rembrandt etchings.

Of course I gave the story everything I had to give. It’s hard science fiction in that the setting is worked out as carefully as I was able and the only perhaps questionable assumption is that certain nonhumans possess a kind of telepathic capability. It’s fantasy in its atmosphere, derived partly from medieval Danish folk ballads. It reflects my interest in Jungian psychology and, yes, if you look closely, Sherlock Holmes. It was well received, winning awards and being reprinted in several different places. But that was long ago, and I trust that by now it will be new to most readers. Let me close this introduction with my introductory remarks way back then.

“The Queen of Air and Darkness” is a figure of unknown antiquity who continues to haunt the present day. T. H. White, in The Once and Future King, identified her with Morgan le Fay. Before him, A. E. Housman had written one of his most enigmatic poems about her. But actually the title—a counterpart to the traditional attributes of Satan—is borne by the demonic female who appears over the centuries in many legends and many guises. She is Lilith of rabbinical lore, who in turn goes back to Babylon; she is the great she-jinni of the Arabs; the Japanese were particularly afraid of kami who had the form of women; American Indians dreaded one who went hurrying through the sky at night. In medieval Europe, one of her shapes, among others, is that of the mistress of the elf hill, against whom Scottish and Danish ballads warn the belated traveler, and who reappears in the Tannhäuser story. Her weapon here is the beauty and—in the old sense of the word—the charm by which she lures men away from her enemy God. Certain finds lead me to suspect that they knew about her in the Old Stone Age, and she will surely go on into the future.'

Thus ends Poul Anderson's final word to his fans. It is fitting that 'The Queen of Air and Darkness' is the end to the book. It illustrates what Poul did again and again in his career: melding his love of the 'Northern Thing' with SF. A whole blog post could be devoted to Anderson's 'elves'--terrestrial and extra--but I'll note that 'The Saturn Game'—which starts this collection—also mentions elves, along with several tales in between.

Poul's 'Northern Thing' goes far beyond ‘elves’. Again and again in his SF tales, he compares someone to a 'wolf' or something to the ‘Northern Lights’. It was simply part of his basic vocabulary. It was in his blood.

I began parting ways with 'Science Fiction' back in the 1980s and don't regret it. Only a small percentage of it since then warrants my attention. That said, I read basically everything Poul ever wrote, SF or Fantasy. Thankfully, he was so prolific, I haven't plumbed that Well of Mimir to its depths...yet. The day when I read my last 'new' Poul Anderson tale will be a truly bittersweet day.

Swordsmen from the Stars recently reprinted some of Poul's earliest, most Howardian/Burroughsian fiction. For fans of sword-and-planet and sword-and-sorcery who are not already Anderson fans, that book is exactly where I would say one should start. For those of us long-time fans, it's still a great read.

All of that said, Going For Infinity is an excellent collection of tales for anyone who appreciates well-wrought fiction. Poul Anderson was one of the twentieth century's masters of the written word. You owe it to yourself to read his works.

As an afterthought... Maybe I just can’t use Google’s Ngram feature correctly, but I can't find an earlier instance of the phrase 'going for infinity' before Judas Priest's "Another Thing Comin' ". If that is correct, I would imagine that someone at Tor Books in 2001-2002 was a metal fan.

Rest in peace, Poul.