Writing With the Dead: Lighting Poe’s Lighthouse

I’ve long been fascinated with the issue of a dead author’s uncompleted works. What should be the fate of the half-finished novels and hardly-started short stories that so many leave behind? It’s a problem that has impacted the legacies of countless notables from Charles Dickens to H.P. Lovecraft, from Robert E. Howard to Frank Herbert to Robert Jordan—the list is endless, really. Authors themselves can have strong feelings about the matter. Some authorize continuations of their worlds and stories before they die, as Anne McCaffrey did with her Pern series, carried on by her son Todd. But others have very different feelings about the idea of posthumous collaborators. Harlan Ellison is said to have instructed his wife to destroy all his unfinished works upon his death; whether this was adhered to I don’t know, but Terry Pratchett left behind a request that the hard drive which held all his fragments should be flattened with a steam roller. This was done.

Obeying the wishes of the dead seems right. But if Max Brod had fulfilled his friend Franz Kafka’s deathbed request, the world would never have read the expressionist classics The Trial, The Castle or Amerika, because they were all unfinished, and Kafka had asked Brod to burn them.

And what if a writer leaves behind no instructions whatsoever?

Though not a lot of people know it, no less a literary eminence than Edgar Allan Poe left behind an unfinished work—the first few handwritten paragraphs of a short story composed in the last months of his life. (You can read it here.) He did not, however, leave any instructions as to what should be done with the piece in the event of his death. Untitled, though commonly referred to as “The Lighthouse,” the fragment takes the form of a diary being written by a lighthouse keeper just arrived at his new position. He records how the lighthouse is constructed. He spends time with his dog Neptune. He reflects on how difficult it was to obtain his job. He remembers two people, De Grät and Orndoff. He wonders if there is “some peculiarity in the echo of these cylindrical walls.” And then…

Well, that’s it. The thing just stops.

“The Lighthouse” languished in obscurity for more than a century. It didn’t appear in standard editions of Poe, and even someone as Poe-obsessed as I was as a teenager in the 1970s had never heard of it. I eventually learned of the tale when I came across a version of it in the early ’90s by Robert Bloch, of Psycho fame—though even Bloch’s 1950s completion was relatively little-known. Still, it was a start. Fired with curiosity by Bloch’s version (which is far more like a Lovecraft story than Poe), I did some research at the University of Maryland’s McKeldin Library, and in a scholarly Poe variorum eventually found the unadorned fragment itself, as Poe left it. I was surprised at how brief it was—Bloch’s version gave no information regarding where Poe’s words left off and his began, and as it turned out the completion was nearly all Bloch. The Poe original was really no more than a shard, a splinter of what might have been.

But my dissatisfaction with Bloch’s work gave me an idea. Why, I wondered, had Robert Bloch been left alone to have all the fun? Why was his version the only version? What would happen if a big group of writers were all invited to complete the fragment in their own ways—what would be the result?

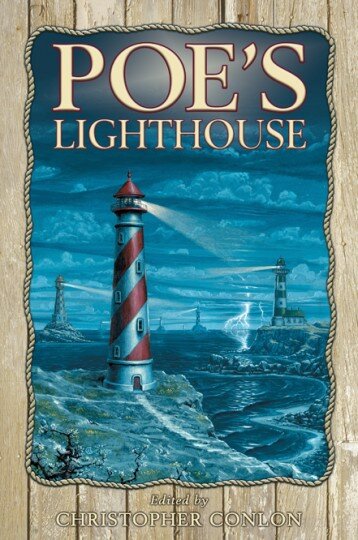

Well, as it happens, my anthology Poe’s Lighthouse was the result. Writers were given free reign to do anything they wanted with the fragment as long as they used it, or at least parts of it, in their stories, and that led to an exceptionally wide-ranging book—Gothic horror, surreal fantasy, mystery, science fiction…it all made its way in through the offerings of some two dozen writers including Mike Resnick, Carole Nelson Douglas, George Clayton Johnson, Earl Hamner, and Chelsea Quinn Yarbro.

Editing an anthology is a complex task, filled with highs and lows. I remember the highs of receiving some of the very best stories in the book, including brilliant works by John Shirley and Richard Lupoff; but also the lows, mostly having to do with authors’ egos and questionable business practices. Maybe the lowest low came when Joyce Carol Oates responded to my invitation to submit a “Lighthouse” completion to the anthology by writing one and submitting it…to a different editor’s anthology.

Anyway, Poe’s Lighthouse was released in 2006 and did pretty well. Its original Cemetery Dance hardcover run sold out quickly enough, and the reviews were mostly strong (Chiaroscuro called it the best-edited anthology of all time, which was pleasing). The book was eventually reprinted in paperback by Wicker Park Press. The anthology is out of print now, but if some enterprising publisher were to want to bring it back again, maybe even adding a few new stories into the mix…well, why not? A “revised and expanded” edition of the book could prove most interesting.

That’s the thing about finishing an author’s unfinished work: there can never be a single definitive version. Any posthumous completion must be, by its nature, speculative. And so the variations today’s writers can create for Poe’s original are literally infinite—in fact, since my anthology appeared there have already been two new movie completions of the tale, The Lighthouse and Edgar Allan Poe’s Lighthouse Keeper. Such new visions and revisions need never end. That’s the eternal truth of writing with the dead.