Mundy Monday: Hira Singh

Robert E. Howard to Tevis Clyde Smith, 22 June 1923: "I found your first letter waiting for me when I got back, also the Talbot Mundy books. I got them Monday. I've read 'King of the Khyber Rifles,' 'The Ivory Trail,' 'The Winds of the World' and have started on 'The Eye of Zeitoon.' [22 June 1923 was a Friday.] How do you like Talbot Mundy? Ranjoor Singh ('Winds of the World,' 'Hira Singh'), Rustum Khan ('The Eye of Zeitoon') and Mahommed Gunga ('Rung Ho!') are my favorite characters, native, that is; a Sikh and two Rangar Rajputs. Did you ever read 'The Man That Came Back' by Kipling? In it a phrase is used, 'Rung Ho! Hira Singh!' which is the titles of two of Talbot Mundy's books."

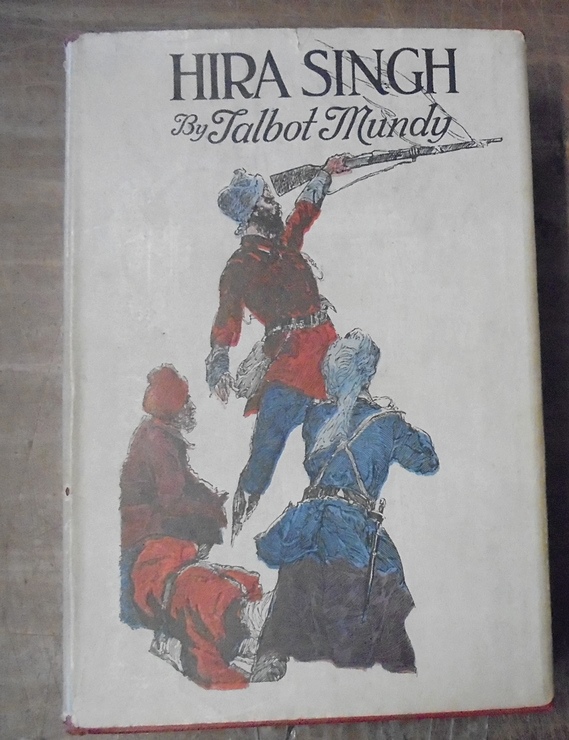

Hira Singh was Talbot Mundy’s fourth novel; his second and third novels (The Winds of the World and King – of the Khyber Rifles) are more properly part of the Greater Jimgrim Mythos of interconnected stories and we will discuss them in their own time. We will also be reviewing the Jimgrim Saga itself (those books whose hero is James Grim) in its own place. Hira Singh was serialized in Adventure magazine in late 1917 and then published in book form by Bobbs-Merrill in 1918. It received mostly positive reviews but many critics were expecting something else, a novel more like his first three books. They didn’t get it; this book is not a romance, there isn’t any element of Eastern mysticism or international intrigue and there are no female characters in it at all. As the author himself said, Hira Singh is first and foremost a tribute to the Indian soldiers who died fighting in Europe during World War I. You can find it in any number of collections or here, at Roy Glashan’s Library.

Partly based on real events, Hira Singh is told from the point of view of a Sikh light cavalryman, a member of Squadron D of the 123rd Outram Infantry (Outram’s Own), the Hira Singh of the title. He describes how he and the other men of his squadron were the first to leave Delhi on their way to the Western Front, 800 strong. Their leader is Risaldar-Major Ranjoor Singh (Singh means lion) and he is the real hero of the story; we will meet him again when we take a look at The Winds of the World. These Sikh cavalrymen journey by rail, then by ship to Marseille where they debark and travel to the front. This is the early part of the war, before trench warfare became the norm on the Western Front and the cavalry of the 123rd are put to good use and help win a resounding victory. Their courage is saluted with song by the Allied troops present, and then the remorseless monster that is the modern face of battle begins to chew them up.

Before long, all of their horses are dead and they must learn a new way of waging war in the trenches. The months pass and while participating in an attack, Squadron D is cut off and their British commanding officers are killed; the command passes to Ranjoor Singh, who decides to surrender in the face of hopeless odds. The Indian troopers of the 123rd lay down their arms and become prisoners of war; eventually, the Germans (who have mistaken the Sikhs for Muslims) decide to transfer what is left of the squadron to their Turkish allies. Ranjoor Singh, who speaks German, has persuaded their captors that they hate the British for spending their lives so freely and then abandoning them. Perhaps their fellow Muslims can use them against their former masters on the front at Gallipoli.

Hira Singh and his fellows are transferred to Stamboul (Istanbul) by rail and then given uniforms, rifles, even back pay by the Germans and Turks in an attempt to win their loyalty. After being drilled as infantry for a time, they are embarked on a small steamer carrying ammunition to the Turkish positions at Gallipoli. This is when Ranjoor Singh makes his move. Using their pooled back pay, the Sikh Risaldar-Major bribes the small crew of the steamer and hijacks their ship. He and his men make it ashore laden with as much ammunition as the men can carry and they sink the steamer behind them to cover their tracks.

Unable to reach the British lines at Gallipoli or the Russian frontier because of the Turkish armies that block their path, the Sikhs head inland. This begins a nerve-wracking journey across the width of Asia Minor and into the mountains of Kurdistan, filled with hairs-breadth escapes, ambushes and raids on Turk supply lines. Ranjoor Singh and his men manage to not only survive but ford the Tigris river and then pass through the lands of the Kurds, across what is now Syria, Iraq and the mountains of Iran. There are engagements with the Turkish army, Kurdish mercenaries and brigands as well as a harrowing depiction of some of the atrocities committed during the Armenian genocide.

Throughout, the story paints a vivid picture of Ranjoor Singh’s qualities as a leader and of the courage, determination and loyalty of his men. The survivors of Squadron D eventually reach the border of Afghanistan with their ranks thinned by combat, starvation and illness; there they manage to impress the ruling Emir with their deeds and with the honesty and diplomatic skill of their leader, and he bids them leave his realm by whichever path they choose. They choose the Khyber Pass and journey through it and into India, the lands of the British Raj, and home.

This isn’t a light-hearted story; there is no romance or humor in it but if you remember that this novel was written as a tribute to the Indian soldiers who died on the Western Front in World War I, I recommend it. It is a quick read and Mundy did a good job of getting me to root for the protagonists. By the end of the story when the men of Squadron D cross the frontier into India, their ranks are greatly reduced and they look like ragged scarecrows; of the 800 men who left Delhi to fight on the Western Front, only 133 have returned alive, every last one of them sick and wounded. A division is waiting to honor their deeds and salutes them with music, the same music they had received in salute when their charge had won the battle that day in Flanders and it moves them to tears.

That music was this song. My grandfathers knew that song; my father and my uncles sang it at the 4th of July picnics my family had when I was a boy. They knew all the words, but I now only remember the chorus. Do our young men and women know this song at all? If we have forgotten this music that meant so much and the men who fought so hard in that war, then I am afraid that we have forgotten something else that is more important than we know.

John E. Boyle is the author of Queen’s Heir and Raven’s Blood, the first two books in the Children of Khetar fantasy series.