Tolkien and Howard: Two Roads Diverged in Haggard’s Kor

Brian Murphy is an occasional essayist and reviewer for numerous web and print-based fantasy outlets, including The Cimmerian, Black Gate, Mythprint, REH: Two-Gun Raconteur, The Dark Man, and SFFaudio.com.

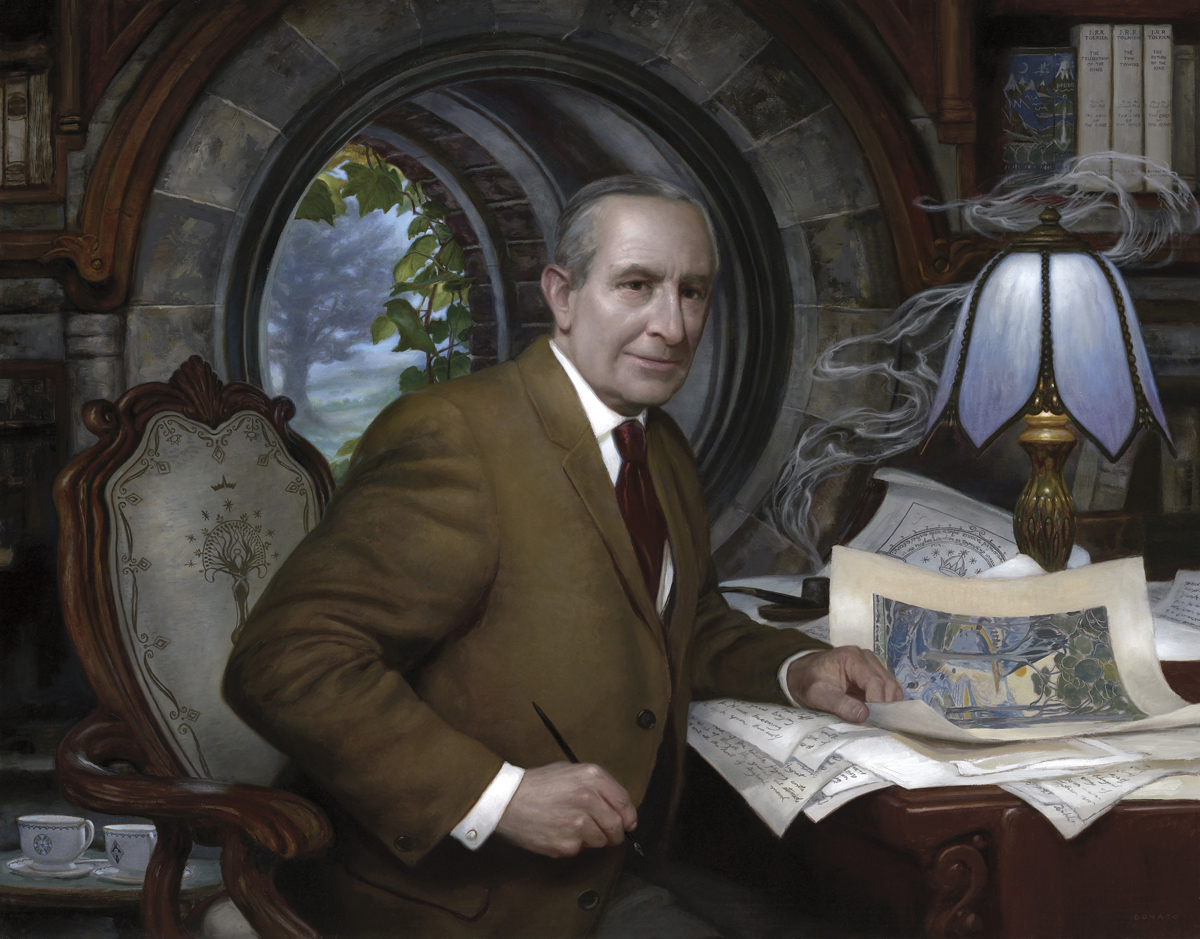

Outwardly J.R.R. Tolkien and Robert E. Howard seem to share little, if anything, in common. The former was an Oxford professor and academic, a World War I veteran whose childhood extended back to the Belle Epoque and Great Britain’s still sprawling age of empire. Howard, meanwhile, was a small college dropout, professional pulp author, and resident of 1920/30s rural Texas, a generation removed from frontier life. Their life work is typically arrayed on opposite ends of the fantasy spectrum: Tolkien is considered the Don of high fantasy, often characterized as possessing detailed secondary worlds of magic populated by casts of characters focused on matters of ponderous, world-shaking importance. Howard is recognized as the progenitor of sword and sorcery, associated with muscular heroes engaged in mercenary pursuits.

Yet the pair on occasion demonstrated striking similarities of thought, particularly regarding the harsh realities of material existence and the concomitant desire for escape. Both for example employed the same metaphor as life as a prison or cage, from which escape was a natural reaction by the feeling man. Wrote Howard:

“A materialistic resignation to unalterable laws is sensible but repellant to me. I will freely admit the necessity and desirability of such a resignation which is no more than recognizing natural laws—if such things be. A man who does not resign himself is like a caged wolf who breaks his heart and beats his brains out against the bars of his cage.”

Compare Howard’s imagery with that of Tolkien:

“I have claimed that Escape is one of the main functions of fairy-stories, and since I do not disapprove of them, it is plain that I do not accept the tone of scorn or pity with which ‘Escape’ is now so often used. Why should a man be scorned if, finding himself in prison, he tries to get out and go home? Or if he cannot do so, he thinks and talks about other topics than jailers and prison-walls?”

Strikingly, both men also use the term “defeat” to describe the inevitable fate of all men, and that raging against defeat was an ennobling act. Howard came within a hairsbreadth of using Tolkien’s catchphrase “long defeat” in a letter to Lovecraft:

“Defeat is the lot of all men, and I come of a breed that never won a war. Men and women too, of my line have fought for hopeless lost causes for a thousand years. Defeat waits for us all, but some of us, worse luck, can’t accept it quietly.”

Here is Tolkien, on the same theme:

“Actually I am a Christian, and indeed a Roman Catholic, so that I do not expect ‘history’ to be anything but a ‘long defeat’ – though it contains (and in a legend may contain more clearly and movingly) some samples or glimpses of final victory.”

It’s not immediately clear where these two very different men developed such similar lines of thought and expression. The most likely answer is a revolt against modernity, which led to developments like the maxim machine gun and the oil field derrick. But another is their literary influences. Tolkien and Howard shared a common interest the works of H. Rider Haggard (1856-1925). Perhaps best known as the author of King Solomon’s Mines and Allan Quatermain, Haggard holds a place of honor in being an important (if not the most influential) forefather of sword and sorcery. In a 1932 letter to Lovecraft Howard listed Haggard as one of his favorite writers. John Garth, author of Tolkien and the Great War, sketches out a brief but amusing episode on the campus of King Edward’s School in Birmingham 1911 in which sub-librarians “called for a ban on ‘Henty, Haggard, School Tales, etc … that can be read out in one breath,’” attesting to Haggard’s pervasive popularity during Tolkien’s days as a student.

Haggard’s She (1887) cast a potent spell on Tolkien and Howard. A popular romantic novel of its era, She featured an ancient city in darkest Africa ruled over by an ageless queen, Ayesha, aka., “She-who-must-be-obeyed.” Howard’s Solomon Kane story “The Moon of Skulls” appears to owe much to She, as does his frequent use of lost, antediluvian cities. As for Tolkien, scholars have written extensively about Ayesha as a very likely influence for his Elf-queen Galadriel, and Tolkien acknowledged a boyhood infatuation with the novel. “I suppose as a boy She interested me as much as anything—like the Greek shard of Amyntas [Amenartas], which was the kind of machine by which everything got moving.”

She contains a great lost city, Kor. Haggard’s description of its cyclopean ruins are echoed in the works of both Howard and Tolkien:

“I know not how I am to describe what we saw, magnificent as it was even its ruin, almost beyond the power of realization. Court upon dim court, row upon row of mighty pillars—some of them (especially at the gateways) sculptured from pedestal to capital—space upon space of empty chambers that spoke more eloquently to the imagination than any crowded streets. And over all, the dead silence of the dead, the sense of utter loneliness, and the brooding spirit of the Past! How beautiful it was, and yet how drear! We did not dare to speak aloud.”

Tolkien wrote a poem directly referencing Haggard’s city entitled “Kor: In a City Lost and Dead,” on April 30, 1915. The poem describes an abandoned city of the Elves and is rife with nostalgia of better times, great civilizations that may still be restored to their former glory. Though no voice stirs within the lost Elven city, its gleaming marble towers merely sleep, “an enduring tribute to its unnamed inhabitants” (John Garth, “The Shores of Faerie,” Tolkien and the Great War, p. 80).

“A sable hill, gigantic, rampart-crowned

Stands gazing out across an azure sea

Under an azure sky, on whose dark ground

Impearled as ‘gainst a floor of porphyry

Gleam marble temples white, and dazzling halls;

And tawny shadows fingered long are made

In fretted bars upon their ivory walls

By massy trees rock-rooted in the shade

Like stony chiseled pillars of the vault

With shaft and capital of black basalt.

There slow forgotten days for ever reap

The silent shadows counting out rich hours;

And no voice stirs; and all the marble towers

White, hot and soundless, ever burn and sleep.”

But Howard had a much different take on what the fate of Kor portended. His abandoned cities spoke of evidence of the decadence of civilizations, and tangible proof of their inevitable fall. Cities are doomed to internal strife, decay, and ultimate collapse, both from corruption from within and barbaric invaders from without. The ruins they leave behind are haunted and menacing. Here is a typical description from “Black Colossus”:

“On every hand rose the grim relics of another, forgotten age: huge broken pillars, thrusting up their jagged pinnacles into the sky; long wavering lines of crumbling walls; fallen cyclopean blocks of stone; shattered images, whose horrific features the corroding winds and dust-storms had half erased.”

As a devout Roman Catholic Tolkien had faith in a final victory—life beyond death in heaven. As an agnostic, Howard’s religious convictions were far less certain. Not surprisingly their depiction of mankind’s works and their ultimate fate differed sharply. From this divergence came one of sword and sorcery’s hallmarks—a concern with upheaval and overthrow rather than restoration of order.

From Haggard’s Kor, two roads diverged in a ruined city—and that made quite a difference for fantasy literature.

Author’s note: The proceeding piece was inspired by a reading of Tolkien and the Great War, in which author John Garth contrasted J.R.R. Tolkien’s reading of H. Rider Haggard’s She and its forgotten city of Kor with Haggard’s darker intent.